The Genocide Centennial concert in Washington, D.C. on May 8 promises to be an inspiring musical event, headlined by leading Armenian artists who have performed on some of the most legendary international stages.

The renowned participants include the Armenian National Philharmonic Orchestra and the Hover Chamber Choir from Armenia; singers Isabel Bayrakdarian and Hasmik Papian; violinists Levon Chilingirian, Ara Gregorian, and Ida Kavafian; pianists Sahan Arzruni and Serouj Kradjian; cellist Alexander Chaushian; clarinetist Narek Aroutyunian; oudists Onnik Dinkjian and Ara Dinkjian,; and David Gevorkian on duduk.

This extraordinary musical presentation is “an expression of rebirth and renewal, and shows that Armenians after 1915 could stand up and create an abundance of culture which is simply astounding,” said acclaimed classical pianist Sahan Arzruni in a telephone conversation.

Triumph of survival

The concert will concentrate on the “Triumph of Survival,” Arzruni explained. ”It is special because it represents all sorts of musicians from all corners of the world, not only Armenian, but also from Europe and North America.”

The concert will focus on Komitas, “the fountainhead of Armenian music who has profiled the music of centuries to come,” and will include “our musical ambassador, Aram Khachaturian, who absorbed Komitas’ music and expressed it in his unique way, a universal way, making it palatable to all nations in the world,” added Arzruni. The program will also feature Alan Hovhaness, “the mystic of Armenian music aesthetically speaking.” Arzruni, who is a specialist on the music of Komitas, noted that Hovhaness was “a disciple of Komitas’, and in an iconic way, he fused Middle Eastern melodies with Western technique that created a language which spoke clearly to many people, a sort of new age music.”

Also featured on the concert program will be the “Requiem” of Tigan Mansurian, whom Arzruni called the “leading composer of Armenia.” The composition was written to commemorate the Armenian Genocide, Arzruni related, and “combine[s] the canonical Latin text with the spirit of Armenian music, thus creating a work of great lyricism.”

Arzruni was born in Istanbul, and until age 21 had never heard about the genocide. “It was never spoken about in our family because later, I learned, it was dangerous to do so.” When he came to New York in 1964, and was staying at International House while studying at the renowned Juilliard School of Music (from which he graduated with bachelor’s and master’s degrees), he met a Turkish student who “approached me and wanted to apologize for the genocide.” On a return trip to Istanbul, he questioned his mother and learned that his maternal grandfather’s family had been “obliterated.” He said, “I became very anti-Turkish, but many years later, have decided that communication is the way to understanding.”

Arzruni is not only a noted pianist, but also a composer, ethnomusicologist, lecturer, writer, and producer. As a Steinway artist, he has performed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the U.S. Library of Congress, the White House, and for many years with Victor Borge. He has appeared on several TV and radio specials, and records for New World Records, Composers Recordings, the Musical Heritage Society, and Philips, among others. In 2008, he was awarded an “Honorary Professorship” from Yerevan’s Komitas State Conservatory.

A united community and outstanding musicians

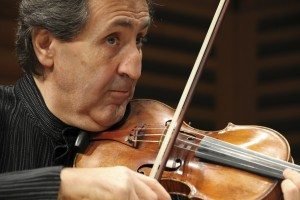

For celebrated violinist Levon Chilingirian, the Washington Centennial is significant for the unity of the Armenian-American community, and for the array of outstanding Armenian musicians from around the globe who will be performing at the concert.

Born in Nicosia, Cyprus, Chilingirian started playing the violin at age 5, and 7 years later came to Britain to study at the Royal College of Music. He won the first prize in both the BBC Beethoven and the Munich Duo competitions in 1969 and 1971, respectively

Chilingirian comes from a talented musical family. His grandfather, church choirmaster and composer Levon Chilingirian, had to abandon his native Constantinople after the Smyrna Massacres in 1922, and take on the post of “tbrabed” at St. James Monastery in Jerusalem. His mother’s family left Adana in 1909, and later for the duration of World War I, before finally settling in Cyprus in 1922. “They would have been exiled to Der Zor had it not been for the violin playing of my great uncle Vahan Bedelian who saved their lives by playing, ‘Alla Turka’ for the music-loving governor of Aleppo,” Chilingirian revealed.

In 1971, Levon Chilingirian founded the famed Chilingirian Quartet, which has performed worldwide. He also serves as the music director of Camerata Nordica, a Swedish chamber orchestra, and is the artistic director of the Mendelssohn on Mull festival. In addition to playing and recording, he is a professor at the Royal College of Music in London.

For his service to music, Chilingirian was awarded the coveted “Order of the British Empire” in 2000.

“Music has been central to our church and in everyday life,” Chilingirian related. “From the wonderful ‘sharagans’ handed down to us through the centuries, to the unassuming folk songs which Komitas notated for posterity, we know that singing, dancing, and playing instruments nourished the souls of all Armenian communities. The therapeutic power of music is exemplified with the fact that one of the first things that Vahan Bedelian created with the newly arrived refugees in Cyprus was a choir.”

He hopes that the attendees of the Centennial concert “return to their communities strengthened by the unified nature of the commemoration. This unique gathering will, I am sure, deepen the resolve of Diasporan Armenians to nurture all aspects of music and the arts.”

Dear Levon Chilingarian,

Did your grandfather, Levon Chilingarian of Constantinople, have a brother named Krikor? The following excerpt is from my father’s diaries of 1915 to 1922 written during the Armenian Genocide. It is an actual account of just one conversation with a little girl named Anoush Chilingarian who escaped. Shiukri was the chief of police of Palu. My father, Misak Seferian, was servant to him for over a year. Anoush survived. I have quite a bit of information about her. Please contact me through this newspaper if you think she may be related to your family. Here is the excerpt.

In the evening, after finishing my tasks, I took the girl by her hand and we left together. I spoke to her in Turkish, but she did not reply. After we left the city, I looked carefully around us and then asked in Armenian, “Nice girl, do you not have a tongue?”

Shaken, the girl stood still and looked at me unbelieving.

“Of course I have a tongue,” she said, as tears spilled down her face.

“Don’t cry my little sister,” I said, and taking her by the hand again, we continued on our way.

When she had calmed a little, I asked, “Where are you from? What is your name?”

“I am from Kghi. My name is Anoush. My father’s name is Krikor, and our family name is Chilingarian,”

“Anoush, do you have any relatives here?”

“Shiukri Effendi brought my cousin with me, but she ran away. I don’t know where she is. The wife of my father’s brother is at Zovia. A Turk took my brother to the summerhouses. He is also my age. We were born together.” She then asked, “Is the hanum a good woman? Do you think that she will keep me?”

“She is a very good woman. She is the daughter of a Kizilbash Kurd and likes Armenians as much as if she were one herself.”

“But I don’t know a word of Turkish, and I don’t understand it. What will become of me?”

“Don’t worry about that. I’ve already taught the hanum a lot of Armenian. I’ll teach her a few more words. I think that will be enough until you learn Turkish,” I said, and we both laughed.

When we arrived at the summerhouse, the hanum greeted Anoush with affection. After serving her food and helping her to bathe, she brought her under the tree where the hanum’s mother and I were picking mulberries. Anoush became a good helper to the hanum. “Anoush, bring a plate. Girl, light the fire,” the hanum would say. Anoush learned to speak Turkish, but unfortunately, she forgot her Armenian in a very short time.