Studying interactions between Armenians, race and whiteness is a challenging historical subject. Some may deem “race” and “whiteness” irrelevant presentist categories for examining processes of Armenian identity formation applied in retrospect to keep up with recent global racial justice movements. Others, meanwhile, may find any discussion of “race” and “whiteness” concerning Armenians embarrassing and even morally disturbing. Yet others may take pride in the so-called “Caucasian” origins of Armenians, claiming organic, transhistorical Armenian whiteness across time and space. Each of these stances comes with intrinsic problems, ranging from race denial to race innocence to racial entitlement, without historicizing the modern white racial construction of Armenians. Consecutive episodes of victimization, beginning with the massacres perpetrated by Sultan Abdulhamid II in the late 19th century and the Armenian Genocide following it, have ossified a lachrymose national self-awareness. Adherents to this mindset have formulated a color-blind notion of Armenian civilizational superiority, rejecting any form of historical speculation regarding Armenian identity. Perhaps the fragile asymmetrical positioning of Armenians in geopolitics and global history may play a part in Armenian race denial or defensiveness or the affinity to “whiteness” and Western civilization.

Are “race” and “whiteness” legitimate optics to analyze the civilizational assumptions wrapped around an ethno-religiously oriented, color-blind Armenian identity? Or do they represent foreign conceptual frameworks that distort our objective understanding of a “genuine” Armenian selfhood? This essay, which draws from my dissertation “Whiteness Across Waters: Domesticating Euro-American Racialisms and Masculinities in the Service of Ottoman Imperial and Communal Subalternities,” will focus on the history of Ottoman Armenian diasporic encounters with “race” and “whiteness” in the United States at the dawn of the twentieth century. I deconstruct what to our ears may sound like non-racialized, color-blind political discourses on the Armenian Question coming from the mouths of Armenian revolutionaries on the East Coast. As this essay argues, based on race and whiteness studies, these Armenian diasporic self-perceptions appear as problematic characterizations rooted in an implicit racialized language grappling with hierarchies of whiteness. The goal is to raise critical awareness of presumably valueless, taken-for-granted notions of Armenian identity and belonging that are deeply racialized and value-laden — cultivated within a particular context, at the height of Euro-American capitalism, colonialism, imperialism and nativism.

It should come as no surprise that a racialized Armenian identity emerged in the harsh nativist climate of the United States starting from the late nineteenth century. Scientific racism and eugenics dictated the rules of American citizenship, reserving political rights for allegedly superior white demographic groups while stripping naturalization and civic freedoms from what were identified to be racially inferior non-white populations. Like millions of other immigrants from Asia, Africa and southeastern Europe, incoming Armenian youth endured the bigotries of systematic racial discrimination in everyday interactions on the streets and at work. Many settled in New York City and Boston, enticed by the abundant employment opportunities in the booming factories of the East Coast, while others largely moved to Fresno for agricultural labor. Lacking a formal education and having almost no competency in the English language, a large group of these men had no choice but to become clogs in the racialized American capitalist machine as menial workers alongside Italian, Irish and Jewish immigrants, relegated to the fringes of whiteness. According to available estimates, around 65,000 Armenians were already in the United States on the eve of the Armenian Genocide and before World War I (David Gutman, The Politics of Armenian Migration to North America, 1885-1915: Migrants, Smugglers and Dubious Citizens, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2019, 4). Their landing at Ellis Island coincided with the arrival of several prominent reform-minded Armenian political refugees from Istanbul and the Ottoman provinces, escaping the tyranny of Sultan Abdulhamid II (r. 1876–1909). In the presence of iconoclast political ideologues such as Stepan Sapah-Kiwlian and Arshak Vramian, the inevitable process of Ottoman Armenian racialization took a dramatically different turn on the Atlantic seashores in stark contrast to the West Coast.

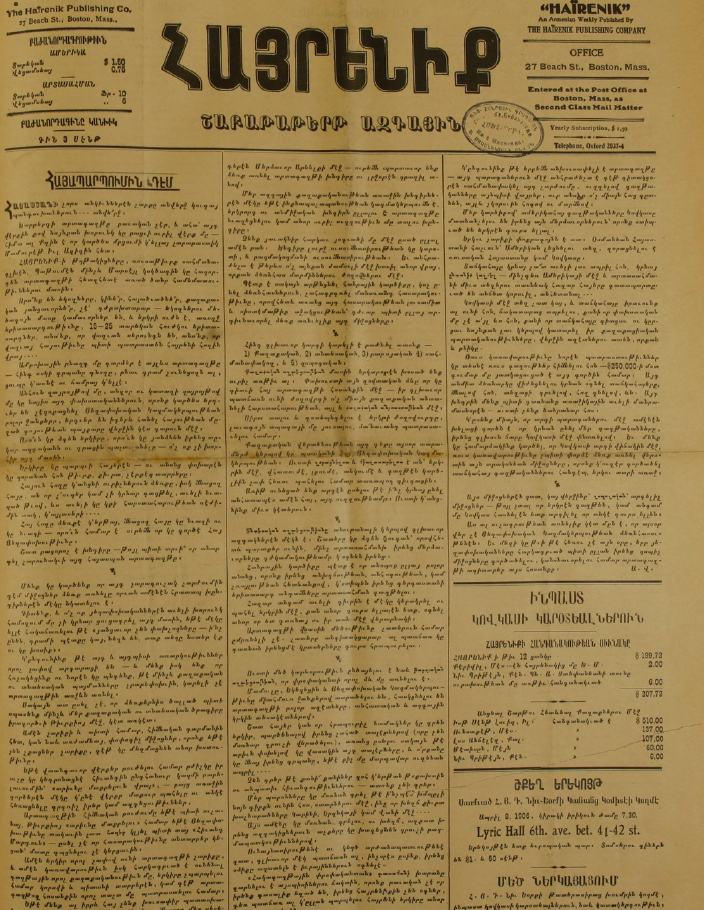

The organs of the two major Armenian political organizations — the Social Democratic Hnchakian Party (SDHP) and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) — promoted a unique, unorthodox migrant assimilation into whiteness on the eastern side of the United States set against Americanization. This was communicated in a color-blind, reformist emancipatory language aimed at fixing Armenians’ precarious relationship with whiteness — not in the country of destination but in the Ottoman Empire. Taken by shock with Armenian racial inferiority, revolutionaries on the East Coast voiced existentialist civilizational dilemmas when discussing the unresolved status of the Armenian Question. On ancestral soil, Armenian diasporic editors, writers and columnists sought to redress asymmetrical power relations between Ottoman rulers and the ruled, perpetuated by the tyrannical, pan-Islamist policies of Sultan Abdulhamid II. They demanded an end to the discriminatory practices that privileged Muslims and justified the subjugation of non-dominant groups under the newly-revived banner of the Ottoman Caliphate. Revolutionaries considered comprehensive territorial and political reforms vital to end the tragic history of anti-Armenian grievances marked by the Hamidian Massacres of 1894-1896 that decimated around 300,000 civilian men, women and children in Diyarbakir and its environs. Meanwhile, the editors of the same Armenian political weeklies, such as Hairenik (the ARF newspaper published in Boston since 1899) and Yeritasard Hayastan (the SDHP’s publication published since 1903 first in Boston, then New York and Providence), strategically chose to remain silent or sometimes even seemed to celebrate the white racial mistreatment of Armenians in the United States.

The color-blind patriotism of Armenian political masterminds in the United States borrowed from white racialist values to reclaim the nation’s right to “life, liberty and honor” as per the provisions of the 1878 Berlin Congress patronized by the European powers. Acting upon pronounced racialized self-consciousness acquired among white American xenophobes in exile, Armenian political warriors aspired for civilizational superiority through territorial autonomy and civic enfranchisement in Ottoman Armenia. Political self-rule in the six Armenian-inhabited provinces of Van, Bitlis, Sivas, Harput, Diyarbakir and Erzerum in easternmost Anatolia became the pinnacle of transnational Ottoman Armenian whiteness. The hierarchical racialist mentality came of age in the oppressive white Euro-American political culture that targeted racial minorities, including non-white immigrant groups, Indigenous nations and peoples of color. The racialist literature of famous European polymaths like Herbert Spencer, Gustave Le Bon and Edmond Demolins was not unfamiliar to Armenian political figures, as it was also commonly read in Ottoman intellectual circles. First-hand racial experiences in the United States, in tandem with curiosity in Darwinian social evolutionist theories, contributed to shaping a racialized Armenian sense of (un)belonging in the United States.

In the Ottoman context, however, the American Armenian civilizational rhetoric promised to advance a formula of Ottoman coexistence and internal harmony against mounting European colonial appetites eying towards the “Sick Man of Europe.” At its core, Armenian leaders’ primary intention was to reemerge as a “political nation” in the example of white civilized nations, as one prominent revolutionary put it, without negating the idea of preserving the Ottoman Empire’s territorial integrity. ARF members, in particular, collaborated with members of the Young Turk intelligentsia in other centers of Ottoman opposition in Europe to accelerate Sultan Abdulhamid II’s downfall. The orchestrated campaign to retrieve the Ottoman Constitution and Parliament, suspended by the same despotic Sultan in 1878, was to set the empire on the right civilizational path. Such a step would have granted equal citizenship to dissatisfied non-Muslim Ottoman minorities banned from participating in imperial governance. Furthermore, the support for Ottoman constitutionalism attests to an urge to preclude the rise of secessionist nationalist movements while protecting the empire’s prestige against potential military encroachments by aggressive European powers. Hence, the racialized, ethnocentric Ottomanism of diasporic activists in New York City and Boston strove to elevate the standing of Ottomans of all stripes vis-à-vis the white global color line that ruthlessly stratified humanity into superior and inferior races.

Unlike incoming ordinary Armenian migrants, fellow Armenians on the West Coast and other diasporic communities in the United States including the Italians, Irish or Jews, Armenian leaders on the East Coast were less interested in the racial qualification of their nationals for U.S. citizenship. SDHP and ARF propagandists such as Sapah-Kiwlian in New York City and Vramian in Boston condemned the continuous waves of transatlantic Ottoman Armenian migration. Both men regarded the long-distance travels of Armenian youth as a blow to the Armenian Question and the chances of inclusion into the family of “white” civilized nations. The physical and mental well-being of provincial migrants vastly mattered to revolutionaries championing long overdue Ottoman political change on behalf of the oppressed Armenian nation. As such, self-exiled Armenian political leaders racialized the migrant male bodies as part of their investment in an inverted, color-blind Ottomanist-oriented Armenian whiteness rooted in the Armenian Question. While incapable of stopping the flow of more Ottoman Armenian migrants from easternmost Anatolia, they offered moral guidance to young Armenian men arriving in the United States. Editorials in the American Armenian expatriate press, such as Yeritasard Hayastan and Hairenik Weekly, attempted to control the social behaviors and sexual desires of otherwise unattended youth in tune with the local racialist ethos (Arshak Vramian, “Hayaparumin Dēm” [Against Armenian Evacuation], Hairenik, April 7, 1906, 1; Sighmani, “Hay Yeritasardě Amerikayi Mēj” [The Armenian Young Man in America], Hairenik, January 12, 1907, 2.) At every turn, revolutionaries reminded these expatriate men of their patriotic duties as the nationals of a reform-seeking ethnic community and the citizens of an empire needing modernization. Accordingly, interracial marriages, especially with Irish women, were prohibited, given their probationary white ranking within U.S. legal regimes. Similarly, Armenian party heads advised their compatriot comrades to refrain from immoral, unhealthy lifestyles including illicit sex, alcohol and gambling that, from a eugenic perspective, weakened the Armenian race.

This American Armenian story illustrates how, in the absence of independent statehood, the Diaspora served as a springboard for ethno-racial sovereignty in the age of racialism, empire and reform. Revolutionaries and activists stationed on the eastern shores of the United States flipped racially oppressive political ideologies to remedy anti-Armenian cruelties in the Ottoman Empire. In the process, they advertently and sometimes inadvertently fostered a racialized Armenian identity expressed in a color-blind lexicon fixated on Ottomanism and the Armenian Question. Nonetheless, as this essay demonstrated, the underlying ethnocentrism was a reaction to the ambiguities surrounding the whiteness of Armenian identity. It replicated the hierarchical world order set by superior Euro-American racial regimes to reinscribe Armenians and the Ottoman Empire onto the white racial map through national autonomy and wholesale reforms.

Be the first to comment