Տիգրիսի Ափերէն Dikrisi Aperen (From the Banks of the Tigris, Dicle Kıyılarından)

Տիգրիսի Ափերէն Dikrisi Aperen (From the Banks of the Tigris, Dicle Kıyılarından)

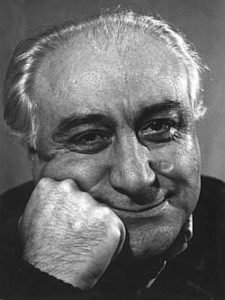

By Mgrdich Margossian

Aras, 1999

192 pp.

Google ‘Diyarbekir’ or ‘Diyarbakir,’ and among the first images you see will be the city walls built by the Romans of the ubiquitous local black volcanic basalt and two iconic bridges— the Ten Arches Bridge and the 12th century Malabadi. All three are situated on the river Tigris. Two are UNESCO world heritage sites. In a way, this Anatolian province and its main town conjure up images of conversion of trade routes, movement of peoples and mingling of religions—all flowing over millennia like the biblical river itself.

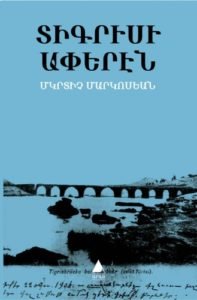

Mgrdich Margossian’s book, however, zooms in on the mundane and the minutiae, cutting a slice of mid-20th-century life in a pocket of this provincial capital—‘Dikranagerd’ or ‘Tigranakert,’ as Armenians call it. Dikrisi Aperen, or From the Banks of the Tigris (though the book has not been translated into English), is a collection of memoirs and musings spanning several decades of the author’s career. However, since the title carries a heavy accent on Diyarbakir and the cover carries the picture of the Ten Arches Bridge, the reader will be forgiven for seeing the book as a single piece of nostalgic outpouring, a goodbye in the form of short stories to the long-disappeared world of post-Genocide, still-cosmopolitan Tigranakert that Margossian grew up in.

Born in Diyarbekir’s ‘infidel district,’ the historic Armenian neighborhood Sur in 1938, Margossian went to the local Turkish language primary school. “We spoke three languages at home: the Dikranagerd dialect, i.e. corrupted Armenian, then Kurdish, and Zazaki,” he says during our virtual interview. He has a grey beard and graciously invites any questions. A calm and kindly man, he credits his brother Ardashes with arranging our Zoom call. The brothers, with two others, including journalist and editor Hrant Dink, co-founded Aras Publishing House in Istanbul, which published the book. Its first part comprises childhood recollections in the genre of village prose or ‘kyughagrutyun’ (գիւղագրութիւն). Dedicated to Lucieh batcho (baji in Turkish), the last of the batchos—or aunties—who “fed us our native tongue, the Dikranagerd dialect,” it has a healthy sprinkling of said dialect and a mixture of Kurdish, Turkish and Arabic words used in the everyday speech of this tight-knit community. It tells a story of the simple existence of Turkey’s shrinking non-Muslim minorities.

In 1953 at age 15, Margossian took a train to Istanbul to formally study Armenian at his father’s insistence. Until then, he had next to no exposure to written Armenian, aside from sporadic tuition by Dikranagerd’s only priest Der Arsen at his house on weekends and during summer holidays. “Anything written in Armenian letters was sacred for us as we only saw them in the Bible.” In one of the stories, the young protagonist sees a discarded scrap of paper on the ground, and despite being unable to read it, picks it up with a view to saving it as a relic: he knows it carries Armenian text. “Like when you see a piece of bread on the ground, you pick it up because it’s a sin to tread on it. I did the same but didn’t realize it was a page from a newspaper…it was enough that it was in Armenian.” I am amused, but he is serious.

“One must needs scratch where it itches,” wrote Robert Burton in his 16th century work The Anatomy of Melancholy. Half a millennium later, that is exactly what Margossian’s book boldly does. It opens with a sketch about a baby’s first tooth celebration in an Armenian household. The baby is going to grow up to be a goldsmith, because of all the things in front of him—scissors, pen, hairbrush, etc.—he chooses a gold bracelet. The father will be pleased: it is one of the best things to be in this melting pot of artisans and laborers.

We are gently guided through a town where Jews, Kurds, Turks, Greeks, Alevis and Armenians live in close proximity to—as well as full view of—one another, albeit in parallel universes, fiercely guarding their own traditions even as they inevitably borrow those of others. Some characters seem ill-formed and lacking in flesh. We get a glimpse of the author’s father, who stubbornly calls his eldest Mgrdich, even after losing several baby sons bearing that name. We are also introduced to his mother, who calls him ‘pasha’ in early childhood. There is a sense of an ‘Anatolian Macondo’ about this community, as Raffi Khatchadourian put it in The New Yorker. Equally, there is a sense of being stuck in time: we see an Assyrian family whose daughter Namo falls in love and runs away with a Muslim Turk. She is then disowned both by her parents and the community, changes her name and adopts Islam. Or an Armenian spinster buries her brother and dies a year later, ostensibly, for the grief of being unable to afford the hospitality expected on the anniversary of his death. There are ‘innocent’ tales of a cat who was a child’s best friend and fellow mischief maker. These only add to the nostalgia and the sense of loss, like the loss of Jews and Armenians who sell up and move away, or the loss of Hredan, the nearby Armenian-populated ancestral village of the Margossians, now called Kirk Pinar and bereft of its former ethnic majority. Hredan, to its natives, had the best figs, the sweetest mulberries and the tastiest watermelons, yet that was not enough to keep them there, against the background of an urbanizing, radicalizing Kurdish Anatolia and an exacting Turkish state. Loss—sometimes too obvious—is palpable, not only of one’s childhood, but of a way of life, in which our toddler was fed hats (bread) in tanabour (diluted yogurt), and as a young man sent to apprentice with his blacksmith uncle.

After graduating from Istanbul University with a degree in philosophy, Margossian wrote a number of literary works in Turkish. In fact, Dikrisi Aperen is his second work in Western Armenian, the other being Mer Ayt Goghmeruh (Մեր այդ կողմերը, 1994), first published as Gavur Mahallesi (Infidel Quarter) in Turkish (1992), then Kurdish (1999), and later English (trans. Matthew Chovanec, published by Gomidas Institute / Aras 2017). “When I started writing in Turkish again, there was more exposure, and people understood the difficulties of the Armenians here better,’’ he tells me. In that, he must have been aided by the documentary Giaour Neighbourhood (2012, dir. Yusuf Kenan Beysülen, Turkish with English subtitles), recounting his return to his hometown—only to find the houses in the Armenian district emptied of residents. The occasion was the much publicized and anticipated re-opening of the largest Armenian church in the Middle East—Sourp Giragos (St. Kirakos). The town’s Kurdish mayor had joined forces with the Diyarbekiri Armenian Diaspora to renovate and reopen the church after 32 years of closure. British actor Kevork Malikyan, or Kazim from Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), is one of them. He makes a brief appearance in the film as a childhood friend of Margossian’s, where they recount their westward migration to Istanbul and efforts to keep their Armenian. There was no resident priest, so one from Istanbul came to conduct the inaugural service. Lucieh batcho, as the dedication in Dikrisi Aperen claims, lived in that church’s courtyard and never parted from Diyarbekir, except when she was hospitalized critically ill in Istanbul, where she died and was buried. Margossian’s parents and uncle are also buried in Istanbul, and from the film, as from the book, a sense lingers of a place deserted, of time shutting its doors on memory, or in the author’s words, of “closing curtains of the past.” The “infidel district” is no longer Armenian, yet in 2009, the authorities renamed three of Sur’s streets after writers from minorities that made it what it was: an Assyrian prose writer, a Turkish poet and Mgrdich Margossian.

If childhood nostalgia is one strand in this collection, internal migration is another. The second part—set mainly on the banks of the Bosporus in Istanbul—includes previously published journalism and deals with the bright lights and intrusive noises of the big city. Once in Istanbul, Margossian graduated from the legendary Getronagan (Կեդրոնական) Armenian High School, whose illustrious students include the linguist Hrachia Acharian, and teachers, the poet Vahan Tekeyan. Another graduate of Getronagan was fiction writer and memoirist Hagop Mndzuri, arguably the last great Western Armenian writer, who died in Istanbul in 1978 and whose own ‘village prose’ soaked in nostalgia depicted life in another Turkish Armenian community, on the banks of the Euphrates. Margossian’s book (or the first part related to Diyarbakir) follows in this tradition, yet for a full picture, the characters could have been developed more and allowed to speak for themselves and their social context with at least as much impact as they do through the author’s statements.

He has been an Istanbulite—Istanbullu—for almost 70 years, and the change he has seen is vast. “I know the former Bolis [short for ‘Constantinople’] and the current one; they’re totally different. Then it had 1.5 million people, of which nearly half were Christians and Jews, but the breakdown has absolutely changed. When I was a [student] at the Armenian school, we studied all the subjects, such as science, etc., in Armenian, but these days there is almost none of that. Armenian Language is a subject they do a few hours a week, while everything else is taught in Turkish,’’ he says. He wrote for Marmara and Zhamanak newspapers, as well as worked as headmaster of the middle school he attended. Ardashes, who followed him to the capital, was one of his students, as was Hrant Dink. The book progresses with broad brush strokes, describing the hustle and bustle of Istanbul of the 1950s and 1960s and the insignificance felt by man in a metropolis. The noise, the crowds, the television—all add to the sense of the author as an observer, but these bitesize descriptions lack narrative or depth.

In a 2013 interview, writer and critic Krikor Beledian, talking of both Eastern and Western branches, said, “Current Armenian literature is in a period of crisis.” This crisis stems not only from a scarcity of younger writers, but also from a lack of publishers—both in the Republic and the Diaspora. Aras appears to have been defying political and economic odds on account of both the quality and consistency of its output since its founding in 1993.

Readers of Western Armenian will feel comfortable with this bedside paperback, and readers of Eastern Armenian will be aided by a lovingly compiled dictionary at the back. Its value as most probably the last book about the last Armenians of Diyarbekir, and most certainly the last incorporating the local dialect, is not to be underestimated. Nor should the author be underestimated, as perhaps the last memoirist of post-1915 Anatolian Armenians.

“Being the last Mohican is not pleasant, of course,’’ he says. “I’ve been in [Armenian] schools in America or Europe, and here too we don’t have [the] ability to develop our language. We could not have the teachers needed. Tragically, there may be few people like us in Istanbul, but we are the last of the Mohicans, yes.’’

Our conversation ends in the same minor key as the book does, the last part of which, the shortest, comprises four letters, ending with an appeal to God. It is a lament, a complaint, a protest on behalf of luminaries of Armenian culture at being left alone, forsaken, sacrificed. Yet the piece is uplifting in that it draws a bridge—surpassing ten-names-strong—between Eastern and Western Armenian literature, mentioning Tumanyan, Isahakyan and Charents alongside Varoujan, Tourian and Metsarents.

Dikrisi Aperen («Տիգրիսի Ափերէն») by Mgrdich Margossian (Մկրտիչ Մարկոսեան) is published by Aras Yayincilik (Istanbul 1999)

This is a fantastic book of short stories. Another beauty of life in Dikranagerd and many examples of its dialect.

Superb, enriching review. Thank you.

A very useful and interesting review and referencing a culture of which I was sadly not enough. It would be terrific to have even a small part of it translated into English. Perhaps… one day.