WATERTOWN, Mass.—Project SAVE has two very good reasons to smile before a camera these days.

Not only is this photographic treasure celebrating its 35 anniversary throughout the Armenian community but it’s also 25 years since the first calendar ran hot off the presses.

It all bodes well with historian-preservationist-executive director Ruth Thomasian who resembles nothing less than an Energizer bunny in her quest toward documenting historic prints in an office at ALMA that’s bursting at the seams.

And short on capital. Talk to her about challenges and the answer becomes redundant. Where there’s a will, there’s a way—trite as that may sound.

“Most of my knowledge of Armenian heritage comes directly from the hundreds of photo donors I’ve visited over these past 35 years,” she’s quick to admit. “They have shared incredible stories that not only document their photographs but often go beyond what the eye can see. It remains our mission to share those stories and impart that knowledge. Our calendar is one of those ways.”

The 2011 edition represents Armenian dancing in all its splendor—from folk to ballet to jitterbug—showing the diversity of social life both inside the homeland and Diaspora.

A wide selection of dance photographs include the personal collections of ballet dancer Leon Danielian of the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, courtesy of his niece Stephanie Zoccolillo and family friend Syruan Palvetzian, and folk dancer Eleanor Der Parseghian Caroglanian, who trained in Soviet Armenia.

Monthly subtopics focus on children dancing, weddings, picnics, the 1964 World’s Fair, amateur dance groups, performance dance and professionals. Each photograph is captioned with details that put it into an historical context and bring the dancers to life.

“It’s our major source of income,” adds Thomasian. “But it’s also a way of sharing our photographic treasure. There’s the ‘mom bar.’ A candle dance. The last dance of a day’s long wedding celebration. The candle is extinguished and everyone goes home.”

Anyone with a social whim should find the venue nostalgic. The Armenian tradition of hantesses and “kef” parties has traditionally brought joy into our lives with the beat of a dumbag, strum of an oud, and hopping about to the rhythm of a tamzara of halleh.

Last year’s theme rolled out the carpet and put the accent on rugs. Previous subjects have included Armenians flying the flag, music, women, military, weddings, classic kids and recreation. First introduced in 1985, the calendars were produced every other year until 1991 when they became annual.

Its history is inimitable. Founded in 1975 by Thomasian, Project SAVE is housed at the Armenian Library and Museum of America in Watertown Square.

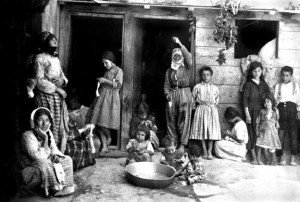

Its collection of historic photographs has burgeoned to 35,000 dating from 1860. Unique in its mission, the center preserves the fragmented heritage of dispersed Armenians through photographs and memories of life in historic Armenia.

Each image is painstakingly documented and catalogue by Thomasian and a staff of dedicated workers, most of them volunteers with a passion toward preservation.

Thomasian spends hours interviewing photo donors as they document their photographs with stories about their lives, ancestors and cultural details. The interviews are taped and become part of Project SAVE’s oral history collection which currently exceeds a thousand hours from nearly 600 subjects.

Along with promoting greater knowledge of the history and culture of everyday Armenians, emphasis is also paid to the lives and works of Armenian photographers.

“It is through their work that so many images of historic Armenian life and traditions were captured and preserved,” says Thomasian. “Our purpose is to make our resources available and increase our outreach to the academic communities, general public and greater Armenian community.”

Not all is picture-perfect, however. Unwilling to rest on any laurels, Thomasian has outlined a vision toward the future:

—Establishing a database of images accessible via the internet

—Acquiring a state-of-the-art facility for archival work, storage, exhibitions and research

—Creating a traveling exhibit for use in museums, schools and other venues

—Exchanging information on methods, policies and standards with similar organizations

—Developing a curriculum to teach history through the study of photographs

—Investigating possible long-term affiliations with an educational institution or an Armenian organization—or with other ethnic archives

—Establishing satellite offices with trained staff to expand outreach in other major Armenian communities, both nationally and internationally.

Much of Thomasian’s time has been spent on the road this year, traveling across the country to cultivate her mission. A recent trip to California proved quite successful as did another to the mid-western communities.

When the Center for Global Education at Framingham State College presented a teacher-training workshop on developing multicultural values, the school invited Thomasian to lead a session on using photographs as cultural artifacts.

Slide lectures at the University of Michigan, Fresno State, Simmons and Wellesley are further complemented by talks at Armenian churches and schools.

In and out of attics and basements she has meandered in search of forlorn images—a veritable scavenger hunt for lost treasure. Nearly half the annual budget comes from individual donors, many of whom also donate photographs from their family albums.

An imposing display of mounted photographs with captions and textboards are being exhibited at genocide commemorations, theatrical productions, cultural exchanges, summer camps and family gatherings.

When playwright Richard Kalinoski needed a vintage Armenian photograph to use as a centerpiece in his award-winning play “Beast on the Moon” about Armenian immigrants and the genocide, he turned to the archives of Project SAVE.

The same could be said for noted author Peter Balakian for the cover of his critically-acclaimed memoir, “Black Dog of Fate.”

So did Atom Egoyan’s research staff for “Ararat,” the BBC television production “The Great War,” Ted Bogosian for his PBS production “An Armenian Journey,” and Leslie Ayvazian, for a photo display during the run of her play, “Nine Armenians.”

“People appear very receptive toward Project SAVE,” Thomasian points out. “They’re looking to grow involved and help us perpetuate our mission. For that, we’re extremely grateful.”

For further information on Project SAVE, call (617) 923-4542 or e-mail: archives@projectsave.org.

May the deniers and their seenseele all rot in jahenem and quickly.

May God give strength and many many years of health to Ruth and her dedicated staff for such agreat work.

We are looking forward to having strong, powerful database of photographs and history behind them.

God Bless Armenia and our people.

Gayane

I have seen “Beast on the Moon” it is a fantastic play, didn’t know the photographs are from Project Save. The main character in the play is a photographer, it is an excellent story that will be playing in Los Angeles in September.

There is also an extensive photo collection of Armenian widows and orphans in the Library of Congress.