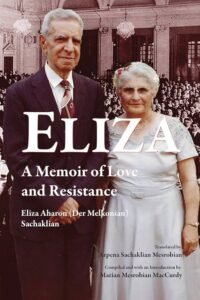

Eliza: A Memoir of Love and Resistance

Eliza: A Memoir of Love and Resistance

By Eliza Aharon (Der Melkonian) Sachaklian; translated by Arpena Sachaklian Mesrobian; introduction by Marian Mesrobian MacCurdy

Published by Gomidas Institute Books

Eliza: A Memoir of Love and Resistance fills the gap in literature about Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. The memoir contributes to both Armenian Studies and Armenian Genocide studies. Eliza Aharon (Der Melkonian) Sachaklian provides a spirited account of her life, from surviving the Hamidian Massacres and the 1909 Adana Massacres, to starting a new life and family in America. Sachaklian details her life as an Armenian child, teenager and spouse. She also chronicles the 1894-1896 Hamidian Massacres, the 1909 Adana Massacres and her interactions with her spouse Aharon Sachaklian, who became one of the leaders of Operation Nemesis that assassinated the leaders of the 1915 Genocide.

The readers begin Sachaklian’s story as she gambols freely, runs races with boys, climbs trees, jumps rope and plays knucklebones as a child in the Armenian neighborhood of Aintab. Sachaklian is unstoppable. In one incident, she climbs with a friend to the second-floor roof of her home to eat grapes off the tall vines, only to stir up a hornet’s nest. She is stung voraciously, drops to the first-floor roof and is rescued by a neighbor, who douses her in a mud bath.

Sachaklian bravely shares her deepest dreams, too. Early in life, she has a fantastic dream of an ascent to heaven. The dream begins when she goes in search of water. She crosses into the home of a Turkish pasha when she sees a pool of water, and a man with a black beard and long white shirt emerges from the still pool. In vivid detail, we read of the angels who carry her to heaven and her vision of God and of a paradise blanketed with grass like green velvet. Had literary paths been more open to Sachaklian, she could have produced works akin to Revelations. Sachaklian describes her dreams as well as her interpretations of these dreams throughout the memoir.

In “Engagement and Marriage,” readers learn that the process of courtship, betrothal and marriage was complex and could vary widely. When Sachaklian comes of age, Armenian women visit her house seeking her hand in marriage for their sons. Her father, however, believed that young women should not be forced into marriage, and after his death, Sachaklian’s mother delivered on that promise. Sachaklian has a crush and dramatic courtship with a boy next door. At one point, the boy’s sister-in-law interferes and diverts the boy’s attention to a rival. Just then, Aharon Sachaklian shows up, admires Sachaklian and proposes. She accepts, and she is refreshingly honest in admitting that she is partly motivated by revenge. The mother of the boy next door complains, and a friend of Aharon – the famous Dr. Bonapartian – tries to convince Aharon to marry his sister instead. In the end, Eliza and Aharon marry and sail for America.

This heated courtship drama – involving the machinations of men and women – counters the notion that marriages in the old country were only arranged, and women, always forced to marry. While no one would deny the forced marriages and even sale of women in the Ottoman Empire (an episode soon to be described), Sachaklian’s narrative shows that betrothals and marriages could also be subjects of discussion and debate, mixtures of machinations and motives, influenced by the dynamics of the place, persons and time.

We also see how much Armenian women had to fend for themselves. The Hamidian Massacres left many without husbands and fathers. The Genocide did so to a tragically greater extent. Even Sachaklian, safely in the U.S., finds that married life is not what she expected. Her husband works long hours as an accountant and then more hours for the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF). As Sachaklian states, “I can say that I raised our children” (page 143).

It is no wonder that she sails to Beirut in 1937-1938 alone with her daughter to visit family members who survived the Genocide. We see Sachaklian hold her own in Lebanon, Greece and Egypt with greedy taxi drivers and difficult travel companions. She negotiates with customs officers, ship officers and porters, under pressure and with skill. At one point, a corrupt policeman harasses Sachaklian, and she and her daughter are saved from real danger only through her bravery and ability to convince the ship’s crew to help.

Sachaklian describes the tragic events that faced the Ottoman Armenians. During the 1894-1896 Hamidian Massacres, Sachaklian’s mother jumps from a high roof while cradling the small Eliza in one arm and her infant brother Melkon in the other to save their lives. They survive. Her father’s shop is looted and destroyed, and Sachaklian’s mother supports the family by selling her prized embroidery. Her father survives by joining the priesthood.

After the Hamidian Massacres, the ARF gains increasing force, along with other Armenian parties. Sachaklian’s family members become passionate Dashnaks. Not long after, her brother Mihran goes to study at the American College in Tarsus only to be arrested and thrown into a Turkish jail when a policeman sees him – an Armenian – opening a letter from Europe. Mihran is locked up with murderers and other criminals, and he is not allowed to communicate with his family or friends. He finally escapes by squeezing through the bars of the window during a prison brawl.

When the massacres break out in 1909 in and around Adana, Mihran is elected the general commander of Deortyol. The people of Deortyol build their defense, with work allotted to both men and women. When the Turkish mobs attack, the men defend the town for three days.

The women march with broomsticks to create the appearance that the Armenians have many more guns than the few they actually possess. On the third day, the Turks cut off the water supply to Deortyol, and Mihran with a band of young men slip out of the town, reach the new dam, kill or scare off the Turkish soldiers and restore the water supply to Deortyol long enough for residents to fill every empty container with water and continue their defense.

In the memoir, we also witness the slow but relentless process of Genocide that reduced the Christian population in the Ottoman Empire from 20-percent to less than one-percent in the span of 200 years. The process involved not only massacres to cut down each generation but also chronic persecution of individuals and local pillaging to steal the Armenians’ lands, wealth and women. In the memoir, an impoverished Armenian with no wife and many children sells one young daughter to a Kurd whose wife has no daughter but desires one. Sachaklian’s father, the priest in this region, intervenes and manages with difficulty to retrieve the girl. He persuades the Prelacy to help the girl’s equally impoverished grandmother so she can raise the child.

Eliza’s interactions with her husband, Aharon Sachaklian, show the personal sacrifices of the heroes who defended their people. While a young mother in Boston, Sachaklian wonders why her husband is absent for a long time. She gathers her infant and defies the cold and snow to take the trolley to the ARF headquarters. Upon seeing her enter, her husband snaps, “Quick, quick, go!” She leaves very hurt and in tears. In retrospect, her husband, who had already been involved in gun running to protect the Armenians, was engaged in clandestine activities. He and the ARF men in the office that night did not want Eliza (or anyone else) to see and hear what they were doing. Sachaklian’s description of the episode shows that the hurt stayed with her for many years, strongly suggesting that her husband protected her – and their children – to the end from knowledge of his extremely high risk clandestine activities.

Sachaklian had the spirit and skills of a Saroyan. She had many books within her. Had she taken the chapters detailing her life as a girl, maiden, bride and mother and added more, for example, on raising three children alone, that would have been a bestseller akin to My Name Is Aram. Then, Sachaklian could have written a separate historical text on the Hamidian Massacres, 1909 Adana Massacres and other important events that transpired during her life in the Ottoman Empire. That book would make a significant contribution to Armenian Genocide studies.

Circumstances, however, conspired to make Sachaklian a ‘girl interrupted.’ The Hamidian Massacres destroyed her town’s life as well as her father’s business and led him into the priesthood. His assignment to the parish of Missis ended her formal schooling, as Missis was so small it had only one school for boys. Sachaklian’s marriage as a teenager brought her to America, where she raised three children practically on her own while her husband worked long hours.

Marian Mesrobian MacCurdy, Ph.D., writes a comprehensive introduction. MacCurdy is Sachaklian’s granddaughter and summarizes her life spanning a century, from her birth in 1889 in Aintab to her death in Syracuse in 1990. MacCurdy shares glimpses of Sachaklian, “the four-foot nine-inch powerhouse who could will a peach pit she had stuck into the ground to grow into a fruit-bearing tree” and “managed to stay who she was after the massacres that destroyed her ancestral home…” (page 54). Sachaklian refused to remain silent in the face of oppression. Sachaklian told her history to many and, in the end, wrote it down to bear witness to that history. “That mission of resistance was a family trademark: from their role in the defense at Deortyol…to her Prelacy Mother of the Year Award speech, Eliza persisted in countering the ongoing persecution of her people” (page 56).

Dear readers, please encourage your library to acquire Armenian books.

Be the first to comment