Special for the Armenian Weekly

When I moved to Armenia in 2009, I had absolutely no intention of meddling with politics. In fact, I made a deliberate effort to stay as far and wide as possible from anyone’s radar—the more undetectable and anonymous, the better, I thought. I moved here to enjoy and support the arts, to fulfill my ambitions in literature and in spreading literature, and to pass on my knowledge to eager students. Of course, I was acutely aware of the fact that arts and literature are (socio-)political by nature, and that what I was teaching involved critical thinking at its core. But I was neither directly involved in politics, nor actively trying to change the status quo. My most rebellious act, perhaps, was teaching a new generation of students to think and to appreciate art and philosophy.

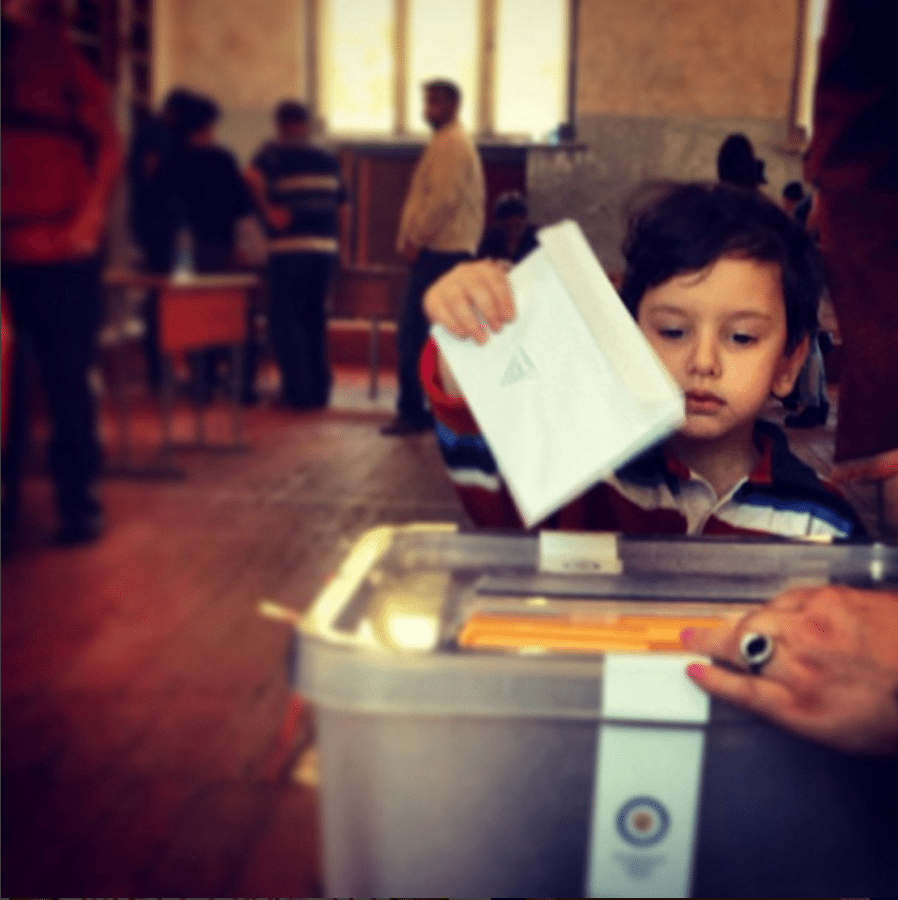

But then something happened in 2013. The presidential elections. Stories of intimidation, ballot box stuffing, and carousel voting flooded my social media feed. Among the storytellers were trusted friends who had been on their feet all day observing the elections and catching one violation after another. Yet, despite all of these accounts, international organizations, such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE), reported that election day was “calm and peaceful overall” and that it was only “assessed negatively in five per cent of observations.”

Only five percent? In my social media feed it sounded more like one hundred percent! So who was I to believe: my friends or international observers?

During the 2008 presidential elections I was still living in Holland—in the diaspora—so it was easy to turn a blind eye and haughtily sit on the fence. It was easy to say: “Well, I’m sure there are two sides to the story. Of course we know—(and here comes the cliché)—that the Armenian government is corrupt, but who knows whether protesters are not just being unreasonably belligerent.”

In 2013, I had already lived in Armenia for four years. I had seen, first-hand, abject poverty, widespread hopelessness, bitter cynicism, and unending emigration. Fair elections and a genuine opportunity for change was all people wanted. That, or, in the very least, a serious breach in the ruling system that would hopefully bring better days for most, sooner rather than later. No more broken promises, but actual, palpable change.

I could no longer ignore the status quo. I could no longer stay apolitical. If I cared about those who were the worst off—for those who had no voice or were afraid to speak up—then I had to actively participate in making a difference and articulate their concerns for them.

When an opportunity presented itself a few months later to observe the Yerevan Council of Aldermen elections, I signed up without hesitation. I needed to see what was happening at polling stations with my own eyes. I could no longer rely on third-party reports, even if they were of my friends or organizations I should trust. More importantly, I could no longer allow myself to sit idly by and let fraudulent elections take place without consequences.

My first experience as an observer was horrible, to say the least. Even though we had been thoroughly tested and trained, from the get-go, my partner and I had absolutely no oversight or control over the snake pit we had been hurled into. Even when we thought we had gained some control over our polling station at one point, it became obvious in the end that we had no idea what we were doing, because we had no idea what they were doing.

They beat us. Hands down. But we were not defeated. Because we learned.

And the first lesson we learned was that even though they played us like a fiddle, our presence alone put a dent in their routine. A tiny dent, admittedly, but a dent nonetheless.

I have since observed four elections; two of them with the same partner I was paired up with the first time. With every passing election, we have armed ourselves with more experience, and thus have gotten better at detecting, preventing, and correcting violations.

During the 2015 Referendum, my partner and I had our polling station under lockdown by noon. Whoever was trying to commit serious fraud knew by noon that they had been defeated. This time, we won. Hands down. And we won, because we understood from experience what to look for and how to stop it.

We caught people trying to vote under different names; we stopped committee members handing out more than one ballot at a time; we stood in the way of young men trying to accompany voters; we used our cameras to record evidence and mobile internet to instantly upload it online; and, by doing so, we put an irreparable dent in their routine—so much so, that they gave up before they even got seriously started.

My most recent observation mission was in Vanadzor during the Council of Aldermen elections. Even though I walked in half an hour after the station had already opened (through no fault of my own), I had the place under lockdown in a matter of minutes. My experience as an observer gave me a level of confidence that had the committee members begging for mercy. My first observation was that the ballot box had only been sealed, but not locked with cable ties. The chairman immediately responded by correcting this violation, which could have otherwise enabled easy opening of the ballot box and, hence, stuffing.

Other observations included the types of violations I had seen many times before: attempted registration of absentee voters, illegal accompaniment of voters, multiple voting, and unauthorized access to the station. The most apparent observation, however, the one I have noticed every single time I’ve observed, was the immediate nervousness of some or all of the election committee members. The fact that they tried—several times throughout the day—to distract me, to ingratiate themselves, to resist me, to argue with me, to raise their voice, to question my rights, and to call the situation “tense” proves that our presence as observers cannot be undermined. If anything, we stand in their way and disrupt their routine.

Imagine if we had not been there to stop registrations of absentee voters. Imagine if we had not been there to have the ballot box properly locked. Imagine if we had not been there to block the same person trying to vote multiple times. Imagine if we had not been there at all.

Am I saying that active observation always works? No. Lights might still “accidentally” go out during the vote count. Ballots might still get stolen or miscounted. Carousel voting might still happen. The point to be made, however, is not whether election observation is 100% foolproof, but rather that it is a powerful tool against fraud and should be used everywhere, at every precinct, during every election, so that even when things do go wrong, when blatant violations are committed, they are filmed and reported as evidence.

Unfortunately, however, even if we are able to keep the polling stations sparkling clean, a much deeper spring cleaning needs to be done outside of the polling stations. Too many people, especially elderly, continue to be bought off or scared into voting for certain parties or candidates.

A prime example in Vanadzor was of an elderly man, who could barely see or walk, coming in and asking the committee members where “number 6” was on the ballot, because that was the number he had to vote for. Even when everyone in the room told him to keep it a secret, to go behind the voting booth, to vote for whomever he wanted, he just would not get it. He took the ballot, leaned against a table, and started looking for number 6. Even when the chairman finally got him to go behind the booth, he still came out holding the ballot in his hand, asking if he had voted “correctly.” This was the most extreme case I’ve encountered in all of my observation missions, but there have been many more subtler ones that indicated a similar pattern of people having been bribed or told what to vote for.

Is it because there are not enough alternative voters to counterbalance bought-off votes? Or is it because more people are somehow enticed to do dirty work during elections? I’ll leave these and similar questions for analysts and experts to answer.

In the meantime, it should go without saying that building democracy goes hand in hand with creating safe zones for fair elections. No matter what happens outside, it is crucial that voters feel safe inside the polling stations and that they can trust that their vote won’t be wasted. And this is why it is so incredibly important to have observers monitoring every polling station, during every election, every single time.

Very infromative and revealing. Thank you Nairi.

“Is it because there are not enough alternative voters to counterbalance bought-off votes? Or is it because more people are somehow enticed to do dirty work during elections?”. Whatever the answer, both problems testify to a deep-rooted corrupt system functioning in Armenian state apparatus and the society as a whole. Corruption in Armenia has taken very sophisticated forms, perhaps much more than elsewhere. Therefore, much greater number of people like Nairi are needed to combat it and prevent the country from going into total ruin.

Thank you for all your efforts to make Armenian votes really count!

On December 3 at Harvard University, NAASR will be holding a panel discussion on the upcoming Parliamentary Elections in Armenia and how the Diaspora can get involved. Professor Anna Ohanyan from Stonehill College will moderate. We will have five panelists including three skyped in from Armenia.

Thank you Nairi for an excellent overview. We in the Diaspora live for the most part in western democracies and would like to see that the Armenian constitution, democratic principles and rule of law are honored in our country even more so. It is our homeland, and we want to see it prosper and not ripped by corruption and lawlessness. We want to not only send money to Armenia but see that human rights and civil society demands are respected, and that we as Diasporans who care so much for our homeland do have a say and are participants in building a nation state with the right values. I think that this is an obligation of all Armenians to be involved and be participant in the democratic process that we all want to see it exists in Armenia.