WATERTOWN, Mass.—On Tuesday evening, Jan. 27, two authors from Istanbul will discuss efforts in recent years to uncover the silence about Islamized Armenians in Turkey.

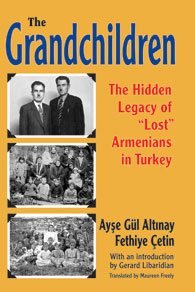

At a reception at the Watertown Public Library, attorney Fethiye Cetin and sociologist Ayse Gul Altinay, co-authors of The Grandchildren: The Hidden Legacy of ‘Lost’ Armenians in Turkey, will present their book, which was released in an English translation last summer. They will be joined by historian Gerard Libaridian, who contributed an introduction to the English edition of the book.

The program is co-sponsored by the Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA), Amnesty International, Project SAVE Armenian Photograph Archives, World in Watertown, and the Watertown Free Public Library.

Fethiye Cetin is a human rights activist who spent years in prison following the 1980 military coup in Turkey. As an attorney, she has mounted a legal effort to find those responsible for the planning of the assassination of Turkish-Armenian journalist Hrant Dink in 2007.

Ayse Gul Altinay received her Ph.D. in cultural anthropology from Duke University and has been teaching anthropology, cultural studies, and gender studies at Sabanci University in Istanbul since 2001. She is the author of The Myth of the Military-Nation: Militarism, Gender, and Education in Turkey.

“Lost” Armenians refers to the fact that, during and after the 1915 genocide, countless Armenian women and children were taken into Muslim households and converted to Islam. In most cases, they subsequently did not discuss their Armenian past, and their children and grandchildren grew up largely ignorant of this aspect of their identity. Over the years, these “hidden” Armenians became outwardly indistinguishable from their Turkish and Muslim neighbors.

The first step in breaking the silence about these Armenians came in 2004, when Cetin created a sensation in Turkey with the publication of her book My Grandmother, in which she recounted the story of discovering the hidden Armenian identity of her grandmother.

In the decade following that groundbreaking publication, hundreds of others approached Cetin with similar stories of discovering their Armenian roots. Several of them have since published books and articles about their experiences and have sought to find Armenian relatives.

Along with her colleague Ayse Gul Altinay, Cetin conducted in-depth interviews with many of these “hidden” or “lost” Armenians; 25 of these interviews have been published in The Grandchildren.

The book thus elucidates an important historical aspect of the Armenian Genocide, as well as its continuing effects on survivors and their families. This is a subject largely overlooked not only by Turkish journalists and historians, but by Armenians as well.

The authors characterize this process of uncovering the hidden legacy of “lost” Armenians as a necessary part of the larger movement in Turkey to reveal the past in order to democratize present-day society. They also point out that hidden identities can be found today in many other nations and peoples.

“As we delve into the past,” Altinay writes, we should not remain ”blind to the many other forms of suffering taking place today.” It is important to guard against “creating new silences, while breaking the silences of the past.”

The book reception begins at 6:30 p.m. at the Watertown Free Public Library, 123 Main St. in Watertown. It is free and open to the public.

Sounds fascinating. I have always wondered about the ‘mysteries’ associated with the Armenian Genocide. My grandfather did not want to speak freely about his escape at a young age, thus I never had a true understanding of his experiences, his journey, and his pains.

Survivors today (asylum seekers and refugees whom I have met and worked with in Maine) are embraced within the community through ESL programs, mentors, and support groups. Had this community awareness and support existed in the 1920’s and ’30’s, I may have had viable stories from my grandfather, rather than resistance to speak of his experiences. I look forward to reading the book

Thanks to the authors exposing this “soft” tragedy on the Armenian Genocide. My grandparents were from Arapkir, a township long since eradicated in northeastern Turkey. There were so many Armenians lost in so many ways because of that unnecessary incursion and mass murder.

This book sounds great I am going to read it!!! Thanks for your efforts

In “The Grandchildren,” we read the (often heartbreaking) stories of 25 individuals in Turkey who discover that they have an Armenian ancestor, usually a grandmother. In the days of the Armenian, Greek and Assyrian Genocide, those who survived the slaughters in the Ottoman Turkish Empire were called “remnants of the sword.” They were largely beautiful women or children young enough to be “resocialized” as Turks. These survivors were converted to Islam by force, out of fear, +/or for lack of having any surviving relatives upon which to cleave. Every conversion may be considered forced because the alternative was death. Some were enslaved as concubines, farm hands or domestics, while others were “married” to Turks in order to justify the confiscation of their family’s lands/wealth, These individual stories are considered a representative sample of a larger segment of the Turkish population that carries some Armenian genes as a result of the Genocide.

One of the editors, Ayse Gul Altinay, claims in her thesis that these descendants of an Armenian ancestor are the “lost statistics” of Armenians who have been disinherited or disqualified by their own ethnic peoples in the Diaspora or present-day Armenia who no longer consider them Armenian. In the estimation of this reviewer, many of the interviewees themselves divorce themselves from their Armenian roots.

Indeed, when the peoples of “modern” Turkey have been indoctrinated through schooling and social structures to believe the “great lie” — that the ancient, native, civilized Armenian peoples of modern Turkey were NOT occupied by Turkic invaders more than 600 years ago but were instead presented as savage interlopers and untouchables in the Turkish empire, this narrative is a very difficult false stereotype to dispel from a Turkish citizen’s worldview…even if that citizen happens to carry Armenian genes.

Quite a few interviewees struggle in vain to discover their family histories, especially in an environment where the ancestors with information to impart refuse to do so out of fear and self-loathing and while the Turkish state suppresses any information that does not align with revisionist ideology. Some interviewees are curious enough about why their ancestor has no relatives of her own, and feel there is a big mystery to unravel. This takes interviewees into many directions (shock and dismay, public ostracization, research into the past, etc). Of those interviewed, a very small sample consider their Armenian ancestry to define who they are.

Nearly all interviews chosen for publication reject the idea of returning confiscated homes and properties to the descendants of native Armenian owners. Is this, too, a representative sampling? Many interviewees — understandably — do not have the tools with which to step out of the Turkish state’s official stance on “the events of 1915.”

When genocide survivors are assimilated into a different religion and culture, that itself is considered an act of genocide. The American phrase “Kill the Indian, save the man” comes to mind. When genocide survivors are put into permanent Turkish bondage; traumatized into silence and refuse to tell their stories to even their own descendants; refuse to use their given Armenian names; refuse to pass on their language, customs and traditions; and are continually belittled for being infidel converts (the word “Armenian” is used as a curse word in Turkey), the psychological damage that results from living in such an oppressive environment — and the mental barriers they create — are often impossible to reverse or penetrate.

Some survivors were too young to remember their roots let alone practice their native customs. Thus, an alien civilization becomes enriched by these ‘infidel converts.’ Personal histories do not appear in Turkish text books and revisionist history becomes the national narrative. Turkey itself does not openly acknowledge these individuals as having Armenian ancestry unless code words are found in official records about survivor converts in order to prevent such individuals or their descendants from advancing in the government or military.

One of the main thrusts of Altinay’s thesis appears to be that these people are rejected because Armenians do not want them. From what we read, it is the interviewees themselves who frequently do not wish to identify themselves as Armenian. The global Armenian community could certainly embrace them, but you cannot reclaim someone who does not wish to be reclaimed.

Based on these circumstances, how can such individuals — who also possess Turkish, Kurdish, Alevi, Zaza or Kurmanji backgrounds — be considered “the hidden Armenians of Turkey” or self-identifying Armenians who are not included in official world population numbers of global Armenians? It is a wobbly theory and epilogue by Altinay for an otherwise eye-opening book.