The Armenian Weekly April 2013 Magazine

(Download in PDF)

Last year, I had the opportunity to travel with my family to Armenia for the first time. The highlight of the trip was visiting with my grandfather’s brother’s family. Upon my return, the discussions we had about our family history spurred me to revisit the genealogical research I had begun more than 20 years ago.

As I reviewed my files, one of the unsolved mysteries grabbed my attention—the story of my grandmother, Pailoon Demirjian, her mother Nevart, and her brother Sarkis.

I never knew my grandmother; she passed away when my father was two years old. I did know my great-grandmother Nevart and my great-uncle Sarkis. However, they never told me the story of surviving the death march from Diyarbakir. I only heard bits and pieces of the story from my father.

Nevart was born in Bakr Maden, and at the time of the genocide was living in Diyarbakir with her husband, Misak Demirjian, and their children, Pailoon and Sarkis. After the genocide, Nevart worked for a missionary as a cook, and Pailoon as a nanny to the missionary’s young child. When the missionary was either reassigned or returned to Canada, they brought Nevart and Pailoon with them. Nevart met a man from Attleboro, Mass. and, once married, moved there. This, plus a handful of old photographs, is essentially what I knew.

When I began researching my family history, before the explosion in available information via the internet, I was never able to determine the name of the missionary. Thus, that is where things stood last summer.

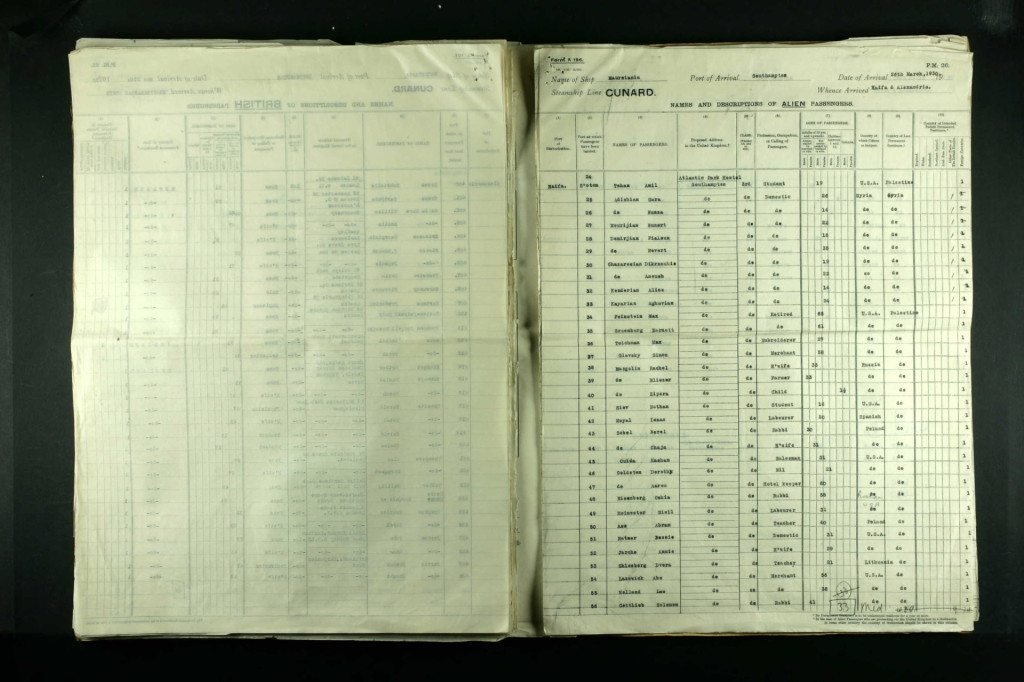

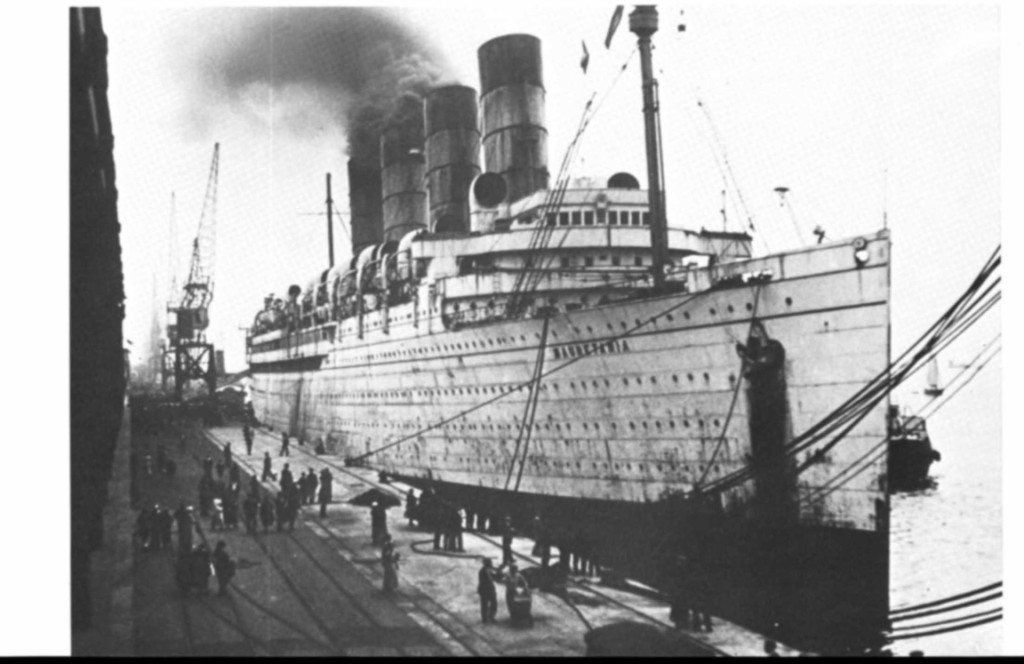

I started by locating the passenger list of the ship on which Nevart and Pailoon arrived in Canada. The website Ancestry.com makes such searches fairly easy, although at times a bit of art is required with the science. Nevart and Pailoon arrived on April 28, 1930 in Quebec on the ship Ascania, sailing from Southampton, England on April 19, 1930. The ship manifest indicated that they were born in Diyarbakir, Syria, and that they were of Syrian nationality and race. Nevart was listed as a housekeeper while Pailoon was listed as a domestic. It also indicated that Sarkis remained in Beirut.

The most interesting piece of information, though, was that they were coming to Canada to see a “friend Mr. Pearce” at 103 Maria Street, Toronto. Handwritten notes indicate that Mr. Pearce’s first name was John and that Nevart and Pailoon were authorized to enter Canada per a diplomatic telegram. I contacted the Canadian government archives, but they indicated such telegrams related to immigration were not retained by the archives.

I was familiar with the story of the Georgetown Boys’ farm, which took in more than 100 Armenian orphan boys during the 1920’s to learn agriculture. The primary person responsible for the program was Rev. Ira Pierce. Was this simply a misspelling, or was Mr. Pearce a different person?

To confirm one way or another, I decided to send the information to some friends in Canada, and asked that they check who lived at 103 Maria Street, Toronto, and where Ira Pierce had lived in 1930. A gentleman from the Zoryan Institute was copied on their replies, and he offered a startling bit of information. As it turns out, along with the Georgetown Boys’ farm project, 39 Armenian women were included in a program to supply domestic servants to Canadian households. The list of 39 is included in the book on the Georgetown Boys by Jack Apramian (republished in 2009 by the Zoryan Institute). Nevart and Pailoon were numbers 33 and 34 on that list!

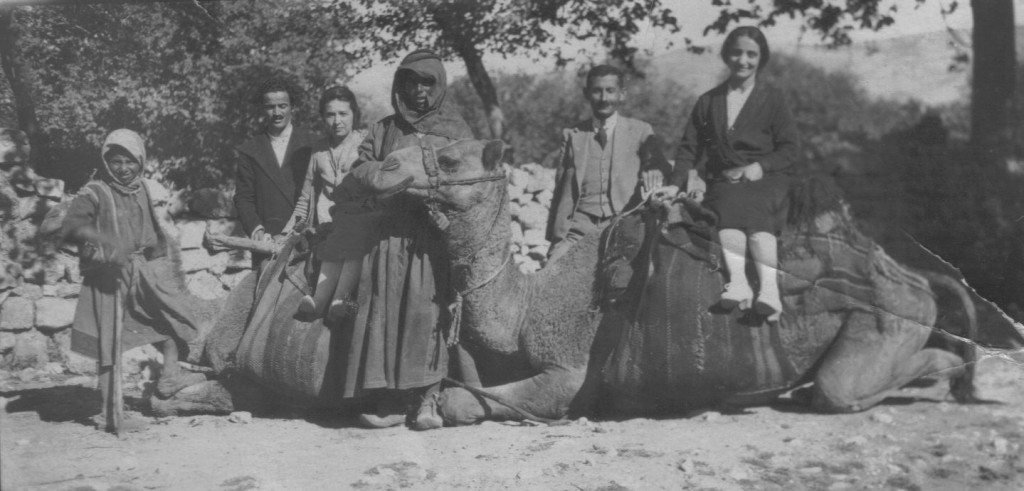

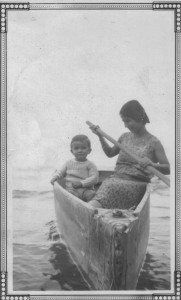

This opened up a history that I had never known, the story of the so-called Georgetown girls (even though few had ever actually resided at the Georgetown farm). The archives of the United Church of Canada contained 13 files on the program and an additional dossier on each of the women. Over the next week, as I was gathering information on the collection, I found a box of photos in the archives catalogue labeled “Georgetown boys,” with the photos identified individually. As I scanned the list of photos, I found “#10 Nevart with our son Alan, #11 Pailoon, and #12 Sarkis.” Unless it was an incredible coincidence, the photos would be of my grandmother, her mother, and her brother.

I ordered copies of all of the material, including the photographs, which were scanned and e-mailed to me. Indeed it was my family!

Who was the young child named Alan? How were these 39 women chosen from the thousands of Armenians in need in the aftermath of the genocide? These were just some of the many questions swirling in my head.

The individual dossiers on Nevart and Pailoon did not contain much information. Pailoon’s dossier dealt with the employers she worked for and some problem she was having with the unwelcome advances from a young gentleman. Nevart’s file mostly contained correspondence regarding her desperate desire to bring her son, Sarkis, to Canada.

A month later, I arrived home to find a box of 500 pages worth of material. Although we had plans for that night, my wife took one look at me and said, “Sit down, read… I will make us some dinner.

A half hour in, I found what I was looking for: a letter from the wife of a professor at the American University of Beirut. The letter recommended that Nevart and Pailoon be accepted into the program, and it made reference to the three photographs that had been in the archives. The letter explained how Nevart’s husband, Misak, had been conscripted into the Ottoman army and was presumed dead. After surviving the death march, Nevart had worked for American missionaries for 10 years.

The author of the letter was of Scottish ancestry, but was born and raised in Syria. She had known Rev. Pierce as a schoolgirl, and I believe that played a major role in Nevart and Pailoon being accepted into the program.

I kept reading through the material, but later did a web search for this couple. I found an article in the Daily Star, a Lebanese newspaper, about their daughter’s return to Lebanon after the civil war to spread their ashes where they met and fell in love. It was now 1 o’clock in the morning, but it was still 10 o’clock on the West Coast where their daughter lived. I called and she picked up! She is now 80 years old, but was not alive at the time Nevart and Pailoon worked for her parents. Yet, she knew of the picture of Nevart with the infant Alan, who was her brother, as a similar picture was in his baby album. In fact, Alan is still alive and living in Vermont! Later, I would have a chance to speak with Alan as well and thank him for all his family had one for Nevart and Pailoon.

There is more to the story, but very little has been written about these 39 women. Over the following weeks, I became obsessed with gathering information about them. I found that two of them had passed away only recently, and was frustrated in having missed an opportunity to speak with them.

I was able to find the list of passenger arrivals into Canada for 35 of the 39 women. One of the women was born in Canada. The program started slowly with two sisters arriving in 1926. It took 3 more years for the next 18 women to arrive before the Canadian government finally agreed to allow a group of 9 women to come. It was this group that Nevart and Pailoon were in.

This group of nine left Haifa and arrived in Southampton in March 1930. While the rest of the group were allowed to continue to Canada, Nevart and Pailoon were held in Southampton; the problem was that Nevart did not have proof that she was widowed. The issue was finally resolved and they were allowed to depart three weeks later.

This would prove to be the only large group of women allowed into Canada as part of the program. The Georgetown Boys’ farm was no longer housing the Armenian orphan boys and Rev. Pierce had taken on a new role in Montreal.

Throughout this endeavor, Rev. Pierce was in a delicate position. On the one hand, he had a lengthy history as an advocate for Armenians. On the other hand, he understood the stringent conditions the Canadian immigration department placed on him, and how the entire program could be compromised when the women diverged from these rules. It took Rev. Pierce years to break through the mentality that “certain races and classes of people…are never likely to be much of an asset to Canada.” [4 January 1926 letter from Deputy Minister of Immigration]

The struggles Armenians were subjected to following the genocide is often forgotten. They were refugees without valid citizenship or passports and, thus, could not travel freely. Canada, like other countries, feared that accepting the Armenian refugees could not be reversed, as there was no country to deport those ultimately found to be unsatisfactory. The so-called Nansen passports were insufficient. Thus, a valid passport, as well as $175 to cover travel expenses, was required of each of these girls.

The Canadian government was also concerned with being a “back door” entry to the United States. This was the cause for objections by Rev. Pierce, often viewed as unfair by the Armenian community, to the potential marriage of some of the women.

The full list of conditions required to secure approval of the potential immigrants follows:

#1 The women must be able to meet the passport regulations and pass medical inspection.

#2 The women should not have first or second degree relatives in the United States, and no relatives at all in Canada.

#3 Any women who had a relative that had not fulfilled their obligations under either the Georgetown boys farm or working as a domestic would also be barred from admittance. On the other hand, every consideration would be given to those women who had relatives still employed in these occupations.

#4 The women would be placed in domestic service under the supervision and responsibility of the Board of Evangelism and Social Services of the United Church of Canada.

#5 The women should not have other family members remaining in the country whence they came.

It occurs to me that my great-grandmother failed on numerous of these points. First, she had left a son behind in Syria in a French-run school. She had a sister living in the United States. Ultimately, she married a U.S. citizen and moved to the United States, thus using Canada as a back door entry.

As one reads through the various papers, the sense of desperation of families trying to reunite, of those grasping for a positive future away from the orphanages, the refugee camps … the desperate thousands in need is palpable. There are also numerous letters from those looking for Armenian women to work as domestics, often in response to articles written by Rev. Pierce in an effort to gain widespread interest in their work for the benefit of Armenians.

There are many layers to the connections between those involved with the Georgetown girls. Rev. Pierce and his wife had been in Kharpert as the genocide unfolded. Margaret Campbell was a nurse also in Kharpert at the time of the genocide who was brought to the Georgetown Boys’ farm as a matron and who adopted one of the girls brought to Canada. Maria Jacobson, Henry Riggs, Martha Frearson, and Elizabeth Kunzler are all names that will be familiar to many for their work with Armenian refugees, and all also worked closely with Rev. Pierce in attempting to bring worthy Armenian girls to Canada.

Today, it is difficult to fully comprehend the meaning of such things. But even with many obstacles, the story of the Georgetown girls changed the lives of 39 Armenian women and their families forever.

Hello George,

I’m so delighted to read your article about your family and the girls.

It’s time that story was told!

thanks for your work and your dedication

Isabel

Thank you, what a beautiful and heart-rending story. The names from Kharpert are familiar. I don’t know exactly which orphanage my grandmother and her brother were in, but I believe they were at Mazrah. My great grandmother had graduated from the women’s college there.

George is too modest. He somehow managed to have authorities open files that had been sealed shut to everyone else. No matter the obstacles that stood in the way, George meticulously followed even the smallest piece of information to its very end. The Georgetown Boys’ farm should now be renamed in order for the title to be more inclusive of the 39 Georgetown Girls. Without George’s unrelenting research, this additional history of those girls would still be in a sealed box, most likely forever lost to us. He has gathered together an astonishing amount of historical data that gives all of us a better picture of the difficulties our survivors faced in the aftermath of the Genocide. My father’s closest friend, Kurken Magarian, was a Georgetown Boy. I remember overhearing his conversations with my father about the hardships and terrible loneliness he endured as an orphan child brought to a farm in Canada by the United Church. These children had lost their families, witnessed unimaginable horrors, and ended up in a country with a language and customs they knew nothing about. George has made a very valuable contribution to the preservation of our history.

Don’t we all Armenians have similar stories to tell?

Scattered all over the world somehow with the grace of God , we still survive and going strong until infinity.

I am astounded at George’s tenacity in pursuing every shred of evidence. In doing so, he has created another valuable resource for some others pursuing their Armenian heritage. If we only knew all the stories of our immigrant grandparents …

Thank you George! Great story. I never heard of Armenian name Pailoon. Only when I finished reading I realized it means shiny in Armenian. I’ve heard of Payliak, the guys version of this name before though.

George – thank you so much for all of your amazing forensic work, and for writing in both a factual and warm manner. Your article brought back vague stories from my own grandparents, and prompted me to do my own digging. Incidentally, I’m always told that my last name is quite rare (Malatyatzi); my father used to kid that somehow we were related to the former NFL great Ben Agajanian. I’m wondering if there’s an Aghjayan connection, too! Sincerely, Marty Ahlijanian

Hello,

We just discovered this website/article as well as the information on the “Georgetown Boys”. We are quite confident now that our father was one of the Georgetown Boys! Do you know where we can obtain further information and/or records? THANK YOU!

Thank you George for all your lengthy research and such a beautiful retelling of your family’s story. I remember my Grandmother Mary Alexanian talking about how they wanted to bring more girls to the farm, but there wasn’t a lot of room to create separate dormitories and not enough money to build another dormitory building. That may account for the reason that many of the Georgetown Girls were placed into domestic service in larger urban areas like Toronto.

My cousin and her husband have created a site with some more pictures of the Georgetown Boys and are looking for help identifying some of the boys. They asked that I pass the link along to anyone who might be interested.

http://www.georgetownboysphotos.com

My mother was one of the girls that came to Toronto, Hermine Garabedian and she married my father a Georgetown Boy. I have my fathers file with his story and letters but not my mothers. Where can I obtain hers?

Hello George

It seems that my mother and her sister may have been the 2 girls who arrived in

1926 to join to older sisters who were already in Canada. I have documents demonstrating their arrival in Halifax in April, 1926 and Mom on several occasions mentioned that a Rev. Pierce was instrumental is getting them to Canada. Mom was placed in a foster home with a Mr. Fred Higgins and all 4 sisters ultimately came to America. If you’d like to pursue their live further, I’d be happy to share what I know.

WOW Thank you George for this wealth of information,it’s fascinating. I wrote a book about The Georgetown Boys in 2019 -THE GEORGETOWN BOYS STORIES BY THEIR SONS AND DAUGHTERS- which was published in September 2019 – I was successful in locating and contacting 11 descendants of the “Boys” who graciously contributed stories about their parents – my book can be read online free of any charges just by Googling “Hrad Poladian” and downloading the PDF – the book has been sent to the 11 sons and daughters and to close friends and to major museums and government institutions. Getting back to the subject of the girls Jack Apramian wrote extensively about the boys but very little about the girls. Through Jack Apramian’s book we learn that Mariam Mazmanian ghirl #16 married Mampre Shirinian. Very little is known about the girls and what happened to them except that most of them worked as servants and nannies. I tried to get information about the girls from The United Church of Canada but was told because of privacy issues cannot have access to those files, all I have in my book is a list of the names of the girls.

My mother #15 Hermine Garabedian her friend Mariam Mazmanian #16 was my mother’s bridesmaid. My mother married #52 Georgetown Boy Khatchig Karajian. Mother’s brother #17 Georgetown Boy Jirair Garabedian. I have my mothers file.