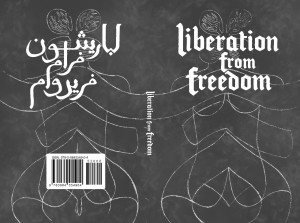

Liberation from Freedom is a book of seemingly opposing words, ideas, world views and belief systems—apparent contradictions about the meanings and abstractions of love, freedom, religion, politics, art, and ownership.

We as human beings in this world have the right to explore, participate, learn, reject, and divest as we see best for ourselves and our growth. It is when we become attached by emotion or obligation to the “other”—the guru, the lover, the family—that we lose sight of ourselves and the continuous improvements we must make to better ourselves and the world around us.

And that is what Kardash Onnig has tried to impart in Liberation from Freedom. It commences with an introduction that promises this is his last effort, and he will not write anymore. It is a bold, fearless, and unapologetic beginning of a book filled with reflections on the Armenians, Jews, President Obama, artists, and philosophers alike that would make most people cringe.

As the author of Savage Chic and Transfourmations—and as the lone Armenian in 1969 who held a sign in Manhattan on April 24 declaring “Unhate a Turk Today”—Kardash Onnig has grown accustomed to the disdain of others. Whether existential, transcendental, romantic, rebellious, or revolutionary, Kardash Onnig finds beauty in everything. The 12 luminaries he cites as inspirations—Nicola Tesla, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Raoul Hague, Henry Thoreau, John Coltrane, and Rumi, among others—have been no more important than the lasting influence of his grandmother, father, and mother. He is an audacious proponent of the art, beauty, and intelligence that has stemmed from what many would consider hearts of darkness. He is inspired by the same philosopher who impelled the destructive regimes of Stalin and Mussolini. Yet for Kardash Onnig, the nihilistic writings of Friedrich Nietzsche symbolize liberty and not the totalitarian bondage imposed by fascism and communism.

He has been an apprentice to those inspirations, having humbled himself in order to learn from those others as part of his process of carving out. Without feeling like a “lesser person,” diminished or demoralized, Kardash Onnig has known there is something to be gleaned from these others, insofar as his own prowess and talents have remained worthwhile. Indeed, someone with awkward discomfiture or an aggrandized ego cannot learn from another without feeling as though his own value is being jeopardized.

By sacrificing his ego and fortunes—walking away from Wall Street, corporate America, the art world, politics, and religion—Kardash Onnig found liberation in the path of least resistance.

Liberation from love

We choose lovers and companions, husbands and wives to whom we have committed our lives. Do we love them enough? Are we sufficiently devoted with our time? Is that person well or whole enough to not fear or mistrust our intentions towards them? Will they enjoy our love until another lover or guru comes along to sway their affection or curry their favor?

Kardash Onnig says all these questions are falsehoods, rooted in faulty emotions that could never be rightly articulated in language. The whole world is a futile struggle of men and words, of semantics and semiotics at ends with each other. Actions, they say, speak louder than those words. And, again, all we have is the present moment to express and show the other who we are—to cultivate, carve out, and burn everything in order to fashion our best, most complete self.

Liberation from art and possessions

Art is not art because it is mysterious, difficult to understand, forbidding, or because someone paid a lot of money for it. A person is not intelligent because of their command of language or their didacticism. So many in the modern art world have made fortunes from their ham-fisted vandalism and defacing—if not outright plagiarism—of others’ styles and works. And then there are those who keep Warhols and Mondrians in their safes or attics, as one would a bond or commodity, instead of adorning their homes with these pieces for their enjoyment and consumption. As such, Kardash Onnig declares that art has lost its meaning and is dead. If a person is going to make it, craft it, write it, or sculpt it, he must know and accept that it is not his once it is transmitted. Its physical form is worthless. Its platonic ideal in the mind’s eye is all that will remain. Therefore whether it is from our own hands or a remnant of another, we should feel free to burn art.

One of the greatest surprises and delights in the book is a poem Kardash Onnig shares at dinner among friends and artists. The erstwhile poet has been reviled by many. Yet this poem Kardash Onnig has found is so incredibly touching and poignant that it leaves one to wonder what wounds are hiding even in the most guarded or sinister of people.

But even that forgiveness and tolerance is based on presumptions from paradigms we have chosen, which ultimately divide us and fragment our own identity and sense of self.

Liberation from the past

Every story needs a dramatic arc, or so they teach us in literature and theater courses. The rising action, conflict, climax, resolution, and then the denouement. And in that last lull, the boredom sets in and we seek turmoil again so that we may resolve it—so that we may be a winner, and the other a loser. Lather, rinse, repeat.

And here is where Kardash Onnig points out our tragic flaw as humanity. For insofar as we look at the annals of history and recite ad nauseam, “Those who do not learn from history are destined to repeat it,” we have in fact replicated all those ills and tragedies in our reality and our distractions thereof.

Through our choosing of politics, faiths, values, or ideologies to identify ourselves, we turned our backs to the world to focus instead on those tribes. We rejected the soul of that which the author has made his name—our Kardash, our brother and friend.

If we carve out from ourselves the negative traits and habits we admit to, we can replace them with the positive ones we identify in the animate or inanimate “other.” We ask ourselves what do those people or objects embody or personify, and proceed to deconstruct and rebuild ourselves accordingly.

Kardash Onnig also encourages the reader to be electrical and attuned to the currents around us. To feel the earth underfoot and the energy that moves throughout all people. To be attached to nothing, but be aware of everything.

The book is a rich, variegated discourse of family history, personal and political struggles, as well as intellectual and artistic pursuits. Kardash Onnig’s voice is reminiscent of Torkom Manoogian, Deepak Chopra, and Eckhart Tolle. His tone is youthful and buoyant as he avoids ponderance or dense philosophizing. He calls himself a fool—and acknowledges that this process in the book is not him expounding on some lifelong quest to find wisdom. But rather, it is exactly what he encourages the reader to do by getting naked, carving out the unnecessary, burning the old, and plowing under in preparation for planting new seeds. The pyromaniac lurking in all of us will delight at Kardash Onnig’s preferred method of disposal.

By writing, expiating and expelling these last vestiges of familial bonds, religion, politics, sorrow, hatred, and anger, Kardash Onnig is at last liberating himself from all the supposed freedoms he has taken throughout his life until this point. By writing this book, by articulating these sentiments in the one modality that all can understand—where it can be concretized in text, and not misunderstood in speech—he can divest himself once and for all of those bonds and burn the bridges that have connected him to those poisons, passions, and persons.

Liberation from religion

The religion we chose has different branches, beliefs, levels of devotion among worshippers, dogmas, and icons. Even as we had sought to embrace a higher power, that entity told us to love only Him—Allah, God, Jesus, Yahweh. Jealous and vengeful gods with rules and limitations on their respective heavens and paradises, and impositions on who his followers can love, associate, and fraternize with here on Earth when that is the only realm we really know—the here and now, the present moment.

One of the greatest issues that Kardash Onnig addresses is the Jews—the cultivators of the state of Israel who deny the genocide of the Armenians while they perpetrate the oppression of the Palestinians. For its terrorism against its neighbors, its people, and its allies, Kardash Onnig likens Israel to a petulant child who will lash out in any direction with unmitigated wanton destructiveness in order to protect itself and its falsely forged identity and its ghettos. And, according to Kardash Onnig, perhaps the greatest victim is this child itself who cannot grow or transform past its borders in the Middle East despite having the largest cultural and religious diaspora. This child that calls its people’s Zionistic duty Aliyah and insists they return to a roughly 8,000 square mile plot of land filled with turmoil and destruction, where on the one hand a bikini-clad girl sunbathes in Haifa, while in Gaza another dons military fatigues to guard a giant cement wall.

Instead of telling them to come and go as they please, Kardash Onnig says Israel’s seething territorialism and possessiveness has destroyed the beautiful heart and revolutionary spirit of Judaism. He says these actions utterly contradict the teachings of forward-thinking, brazen ideologues like the prophet Elijah in which Judaism is rooted.

A tearful goodbye

He concludes with a quote from Jean Rostand that ponders, “Kill a man and you are an assassin. Kill millions of men, and you are a conqueror. Kill everyone, and you are a god.” And indeed, without the gravitas and literal murder of all mankind, this is the truth that Kardash Onnig has discerned: that nothing really belongs to us, whether as individuals, ethnicities, races, and tribes or otherwise. Nothing is ours except for ourselves. Religions, love, friendship, family—these are all trappings themselves whose inner machinations further mire us in the world of words and language, and confuse us as to who we are—which is everything and nothing at once.

And thus, Kardash Onnig ends his last washing of hands not with a triumphant valediction or a proud declaration that he’s loosened bonds or solved puzzles. Quite the contrary, he ends in sorrow for all the things that this three-dimensional thinking and observation have demonstrated and proven. Sorrow that we are all universally conflict-seeking people who are afraid to find comfort, and instead choose a familiar bed of nails. Sorrow for being one of a small handful of people to walk away from the Towers of Babel around the world.

It’s not too late, though. We can still burn.

Be the first to comment