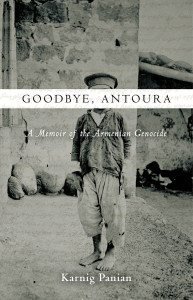

Goodbye, Antoura

By Karnig Panian

Translated by: Simon Beugekian

Stanford University Press, Redwood City (April 8, 2015)

ISBN 978-0804795432; Hardcover, 216 pages, $25.00

Special for the Armenian Weekly

When discussing the significance of publications about the Armenian Genocide during the Centennial year of the crime, it is vital to understand the importance and sheer value of memoirs and first-hand accounts of the time. Though often harrowing to get through, genocide memoirs prove to be important reading to those attempting to get a better understanding of the crime.

Survivor accounts not only allow readers to get an in-depth look at a genocide, but can also be interpreted as acts of resistance against the attempt at annihilation.

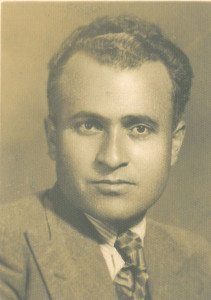

The year 2015 saw the publication of Karnig Panian’s story in English. Panian was a long-time educator and the vice-principal of Beirut’s Armenian Lyceum (Djemaran). Published twice previously in its native Armenian by the Hamazkayin Press and the Armenian Catholicosate of the Great House of Cilicia, the English translation of Goodbye, Antoura was published by Stanford University Press in April. Skillfully translated by Simon Beugekian, who translated Malkhas’s classic Armenian novel Awakening (“Zartonk”), which was recently published, the publication of Goodbye, Antoura makes Panian’s story available to a wider, English-speaking audience for the first time—something that was long overdue. With this publication, Panian’s story is added to a long list of survivor memoirs, which serve as historical proof in the face of the continued denial of the Armenian Genocide.

Through Prof. Keith Watenpaugh’s introduction and afterword, readers are able to place Panian’s story in the greater context of the Armenian Genocide and World War I, while Dr. Vartan Gregorian’s heartfelt foreword outlines the significance of the memoir as a way to never forget the suffering genocide survivors endured.

Panian was born in Gurin (presently Gürün, Turkey) in 1910. Early on in the book, the reader is transported to Panian’s world of cherry trees and childhood bliss in his native village, a prosperous land of hardworking people and a thriving family. Panian’s descriptions of pre-1915 Gurin is nothing short of paradise: a Garden of Eden of sorts, seen through the eyes of a five-year-old completely immersed in Armenian life and brought up to possess a deep love for his family and his people. Panian’s Gurin is juxtaposed against the treacherous Syrian desert and the orphanage at Antoura, Lebanon—the horrors of which he would endure soon after.

Panian’s descriptions of the hardships suffered in the Syrian desert at the hands of Turkish soldiers are deeply disturbing. Though he was only a young boy at the time of the deportations, he is able to recall and paint a grim picture of the physical and emotional despair he and so many others had to endure with great detail. “These people, who just weeks earlier had been prosperous, living in their homes, praying in their churches, working in their fields, and helping the less fortunate, had been turned into a race of emaciated semi-corpses. They were like plants that had been uprooted and cast aside, and they were now dying slowly, shriveling into nothing,” he writes, describing his forced march through the desert alongside his mother, sister, and grandfather.

After the death of his family members in a refugee camp, Panian was taken to the Antoura Orphanage, where surviving Armenian children were systemically and brutally conditioned to be raised as Turks. The orphanage—which was used as a center for Turkification—was the brainchild of Jemal Pasha, one of the architects of the Armenian Genocide. There, orphan boys were completely dehumanized and stripped of their cultural and ethnic heritage—they were given Turkic-Muslim names and brought up to feel as though being Armenian was a shameful disgrace. “We were all humiliated, reminded that being Armenian was a punishable crime,” Panian writes in the pages describing the orphanage.

Between 1915 and 1918, 300 of the 1,200 Armenian orphans at Antoura died under deplorable conditions of famine, disease, and cruel forms of punishment. Despite the horror, though, Panian inspires his reader through his descriptions of the orphans’ desperate desire to hang on to their Armenian identities. “It had been three years since we had been moved to the orphanage, and, clearly, the administration’s attempt to Turkify us was a miserable failure. When we challenged the teachers or the headmaster, we never felt alone. We were one united front, struggling together.”

Panian describes a group of boys who, even in the darkest and most hopeless of times, is able to endure and persevere through camaraderie. “In Antoura, we fought a battle against an enemy intent on destroying our identities. We didn’t have mothers or fathers, or even good teachers and educators, to guide and impart their wisdom. The older boys were our role models. We took our cues from them, realizing that they did their best to be good examples. They encouraged us to keep our language alive, pray to our God, and never forget that we were Armenian,” Panian writes.

Though surely dark at times, Panian’s journey to salvation and his eventual transition into a leading intellectual and educational leader in the Armenian Diaspora is an adventure steeped in hope, courage, and optimism. His descriptions of the horrors he was forced to live, coupled with the hopefulness that his new life promised after Antoura, makes the English translation of Goodbye, Antoura an invaluable addition to the already rich library of genocide memoirs that give the survivors a voice.

In Goodbye, Antoura, Panian says the Ottoman Empire was “silently enacting its genocidal plan before the indifference of the world.” A century later, it is difficult for the world to remain indifferent to a story so brilliantly brought to life through his words.

Thank you for keeping alive the memory of all those that underwent the attempt to wipe them off the earth. And thank you to those that did survive for their courage, steadfastness and undying faith.

This appears to be an important addition to all before it – especially with (my recent) awareness of the orphanages run by Turks to ‘cleanse’ the children of any Armenian identity. I also was impacted with the strong contrast in the review of what the children’s lives had been pre April, 1915, and what they experienced after, turning them into nearly unrecognizable near-corpses. Those of us growing up Armenian already know of these contrasts, but for others, it is a drastic contrast of what the victims and survivors went through. Bless the inner strength of these orphans, and the guidance of their older models.

The translator’s name is misspelled in this article.

My maternal grandfather was born in Gurin. We are hayrenagitz.

Mr Panian I admire your courage and resilience to survive against all odds.