–Sabah El Khair Abu Omar,

–“Good morning to you, Ya Baron,” he responded, laboring to display his vegetables.

It is that time of year again, when the greengrocers pile up fresh green peas delivered directly from the fertile fields of Lebanon. They’ll be stewed in almost every kitchen with cubes of mutton, fresh tomatoes, carrots, onions, garlic, and spices, and served with rice and fried noodle pilaf or bulgur pilaf, simmered in sheep butter, a handful of chickpeas, and sprinkles of black pepper, if you are Armenian. As I fill my cheap non-degradable black plastic bag, I recall two things (as I always do when I see green peas, be they fresh, canned, jarred, or frozen in plastic bags of corporate brands)—that is, my mother’s recipe, perfected thoroughly from macho criticism, and Madame Lucy’s servings as the only alternative to my mother’s home-cooking years ago, when I was just an observant little boy.

Madame Lucy was an Armenian woman with a helmet of dark brown hair. She wore dark eyeglasses in white frames, was short and husky, her fashion insignificant, her lips always painted bloody red, shouting and yelling, smiling and charming, always waiving her right arm and trying to control her left, which had a mysterious history and was replaced by a prosthesis that extended into a skin-toned yellow leather glove. She had an iron-fist control over her troop of cooks, busboys, waiters, doormen, chaperones, shoe-shine boys, coat girls, bartenders, musicians, and clients. They all obeyed her as the goddess of lust. At times her artificial arm moved on its own, and the right one had to force it down to its place, much like Peter Sellers as Dr. Strangelove in Stanley Kubrick’s film “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb” (which, incidentally, I saw in the Bleecker Street Cinema near New York University years ago).

My childless godfather, Uncle Baghdasar Kupelian, who we called Baghdo and was married to my paternal aunt, was a headwaiter in this cafe-bar-restaurant-nightclub-cabaret-brothel all bundled in one, and found in a two-story underground hush-hush den without a sign but known as “Madame Lucy.” This hard-working man had fallen on hard times when Syria was making inroads with one coup d’état after another, until the experiment of a united Egypt and Syria came to an end, paving the way for the Socialist Baath Party to take over the country by nationalizing private wealth (and making owners run in their pajamas to the comfort of their bank accounts in foreign lands). After serving as the head of the Bosch Family’s household servants for many years, and managing nearly 60 people, he was let go with the rest, as the families of brothers Rudolf and Adolf brothers scattered across Europe.

Baghdo already had a reputation by then; people would know if a grocer or a food supplier or a butcher or a baker was good if Baghdo shopped there for the aristocratic family with Austrian roots that had been living in Aleppo for nearly three centuries. In fact, Rudolf was the honorary consul of Holland at the time. Baghdo was the head of wine-and-dine protocols and manners when Rudolf was entertaining heads of states, kings and princes, diplomats, and ambassadors. He made sure the linens were white as snow and the silver utensils were spotless, that the handmade china was dust-free, that not a bread crumb was left behind, no fly entered the room, and no guest left unsatisfied. Most of all, he made sure that Rudolf always smiled.

When Baghdo needed a job, Madame Lucy was quick to offer him a position as the head waiter of her joint, which operated at all hours of the clock. Business was thriving then; the new socialist secular rulers had no problem with alcohol, and they needed to celebrate their newly gained victories. Madame Lucy, like the former ambassador, was entertaining fallen and newly risen men, politicians, party operatives, journalists, intellectuals, agents, and the like, who found commonality in lust and forgot their differences while enjoying their adventurous nights. Nothing new to Aleppo: This is where Lawrence of Arabia, Frey Stark, and Gertrude Bell, among many others, made the city the center of their secret operations. They partied all night and slept during the day at Hotel Baron, which was owned by an Armenian named Mazloumian. Guests included the likes of D.H. Lawrence and Agatha Christie, with countless imaginary crimes in her mind, Iren Papas and Pier Paulo Pasolini, converting Medea into a film, and Hafez al Assad, partaking in a coup d’état. And the list goes on. But at Madame Lucy, there was no guest book, no check-in procedures; the names were hushed and unspoken. In this dark underground “heaven,” Baghdo toiled all day until midnight, then walked home for lack of public transportation, leaving behind a world he could never be a part of—where the wretched souls of natives, Bedouins, Egyptians, Turks, Moroccans, Lebanese, Greek, Armenian, and Jewish women kept the hunger of their families at bay by feeding the desires of aching men.

Normally I wouldn’t have been allowed to descend into this Bacchanalia, but uncle was there and so my entrance was not a surprise to anyone. To the contrary, mine was a rather kingly arrival: The women welcomed me in their laps, pressing my head against their breasts perfumed with smoke and sweat, while the men shook my soft and tender hand. From a tiny boy’s shiny eyes, the place seemed very large. The floor was white, and there were booths with red velvet couches covered in transparent plastic, ugly rubber plants, and tables abundant with food, buckets of ice, and Black Johnny Walker or White Horse whiskey bottles. (The number of bottles indicated the number of women; the rule was that a man opened a bottle for each woman.) I remember clouds of smoke, chitchat and giggles lost in the noise, hands emerging from under tabletops, stolen kisses, a sip of a drink, and a cigarette waved in the air between red fingernails and crimson lips meeting Ronson Varaflame or a DuPont Premium lighter flicked by a fat, manly touch. The bold and grayed men always drew great pleasure from such gentlemanly deeds, which belong to a different era gone altogether.

The circular tables were covered with white linen and decorated with drops of grease; imprints of red lipstick slept on the cloth napkins like broken hearts; and a lattice of red, white, blue, silver, gold, and green tinsel hung from the ceiling, giving the company a sparkling glamour. A large fake crystal chandelier hung from the center of the dance floor where drunken souls danced, holding each other tight, sweeping their bodies left and right, or rubbing against each other carelessly by stepping wrongly to a samba, rumba, cha-cha-cha, or a tango imported from far-away Argentina. Almost always the men were drunk, and the women stunningly alert, as if they had absolute immunity from alcohol.

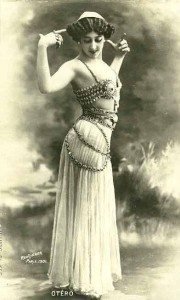

The ageless, lovelorn songs of legendary Arab dames Umm Kulthum and Asmahan screeched passionately through the loud speakers and overused asphalt LP’s. They were followed by interludes of Drbakeh solo for the almost-naked woman draped in colored nets or a transparent veil, with shiny copper zagats fixed on her thumb and middle finger. She’d throw her Amazonian hips from the north pole to the south to the speed of light, or gyrate them in the air from east to west with the speed of a snail, or suspend the move in mid-air depending on the master’s beats on the membrane. Her bare, hefty breasts would be covered with a pair of buttons with loose thread glued to her nipples moved in a magnitude that could have busted the Richter scale, witnessed by the musicians with their half-shut eyes and burnt cigarette residue falling like diamond ash on their instruments. When done with their sessions, they’d retire from their wicker chairs for a meal as the helping hands cleaned the spoils and fresh talent arrived to continue the masquerade. If they weren’t yet tired, they’d play jazz to entertain themselves, and to repent for being cabaret musicians instead of artists in concert halls.

My welcome greetings lasted a second, or minutes, depending on the action around the tables. If their behavior was something I shouldn’t be witnessing, I was whisked away by a free hand who kept me busy with silly questions or bad stories in words and languages I could not make sense of. At times I ended up in Madame Lucy’s lap. She loved me dearly with her good, fleshy right arm and fluffy palm. She’d take off my hat, adorned with two small rooster feathers, and my long grey and black winter coat—attire that was bought for me by Baghdo and Aunty Mary for a portrait they wanted to have done in the famous Studio Arsho, which was selling the new trick of printing photographs onto porcelain plates. Every time I went to their home, I’d stand there and look at the dish with me frozen in it. Was it really me? Is that how I looked like in a hat and coat? Many years later, when I discovered Humphrey Bogart and Al Capone, I instantly recalled that dish on the wall with cracking azure plaster. I guess the childless couple wanted me to resemble a star. Famous or infamous, it didn’t matter; they likely didn’t know the difference anyway.

The men in Madame Lucy’s den always liked my older, elegant look, which reflected their own outfits slung on the couch or perched on hangers near their boots. “Look at this future gentleman,” they’d boast to their female companions, who’d respond by throwing words at me: “Ya Sghaiar, ya sukar, ta’alla ‘alshan baousa lal tunt” (You little one, come here for a kiss from aunty). I was like the little baby in a stroller with his parents out for walk, dog on leash, who’d grab the sudden interest of a strange couple on the sidewalk, speaking to each other through an innocent third party: “What a cute baby! How old is she?” Or, “Is it a boy? What a cute dog! What’s the breed”? These were the idiotic commentary-questions that served to fill the barren moments of the inadequately engaged couple. Neither the dog nor the baby was aware of their innocent participation in salvaging adult complexities of social behavior. Perhaps the dog wanted to get to a post and spray the liquid personality, or the baby was filling his diapers. As for me, I wanted to run to the food to quench my appetite, and then run to the cinema to watch a black-and-white film.

I maneuvered myself to the long table covered in green felt, the only thing at my eye-level with large bowls of food covered with silver domes. Without fail, one of the waiters would lift the domes one after the other to reveal what was kept neatly beneath them for me to choose. Roasted leg of lamb, no. Eggplants stew, no. Baked chicken breast, no. Grilled lamb berzola with twice-cooked potatoes, no, and no, until arriving to my savored green pea stew and Uncle Ben’s rice pilaf cooked with butter and a dash of salt. I would sit at one of the large booths all by myself and indulge in the pleasure of being served. My frame was small, and the quick delivery of red velvet pillows under my tiny back helped me to reach the plates. With a fork, spoon, knife, and white linen napkin next to my dish, I took a good look at the green peas, the dices of carrots swimming in a healthy red tomato sauce, and the shiny rice grains. I rubbed my hands together before holding up my utensils and expressing my tummy-born enthusiasm. Baghdo was always proud of my table manners—that I ate with my mouth closed, and without rubbing my tongue between my cheeks and gum. After washing up, I was ready to be deposited by Baghdo at the Cinema Hamra to watch the film being shown that week. Tucked again in my coat and hat, we crossed the street. He purchased my balcony seat, bought me a bag of freshly made salty popcorn, and led me in to be mesmerized by Chaplin and Lloyd’s “Suddenly, Last Summer” or Jules Vern’s “Mysterious Island.”

One day my paternal cousin Sonia showed up from Beirut to spend family time with us and nurture kinship. She was about my height, slender with boney shoulders, not talkative, not beautiful enough to be impressive and not ugly enough to be interesting. In charge of hosting her, I took her hand to walk through the streets, planning to stop for lunch at Madame Lucy’s. She was stubborn in her refusal to hold my hand, while I wished to imitate the images I had seen on the screen. Her rejection pissed me off and I could not look at her; instead, I kept my eyes low, watching the ground and her white shoes and short white socks with small white cotton pom-poms around the rim. I also caught glimpses of rotten watermelon peels and dead roaches, and a cat or two picking from a metal garbage can, going through shredded magazine pages, pieces of newspaper, the skeleton of a consumed fish, and items that organically belonged on the dirty filthy streets—until we reached Madame Lucy’s. I introduced her to my uncle, who welcomed us joyously with a wide smile and gave us a table, but she vehemently refused anything that was offered. Protesting the kindness, she even tried to turn my dish upside down; I barely managed to prevent the food from spilling over and spoiling my green pea fun. When the ladies approached us with tender greetings, Sonia was repulsed and disgusted. Baghdo was quick to rescue me. He took me aside and, talking in my ear, said I should take her to a film instead, and slid a few Syrian paper liras in my palm.

We crossed the street on our own and as Baghdo had instructed, I bought the tickets and two bags of “Manfoush Puffed,” as popcorn was called back then in Aleppo. And so we were in Cinema Hamra’s empty balcony for the 3 p.m. screening. Once the curtains parted, the coming attractions marched in front of our eyes, and the main black-and-white film, “Lady in a Cage” starring Olivia De Havilland and the very young James Caan, commenced. Sonia rebelled, throwing her popcorn bag away, sprinkling the empty seats and the floor with the white stars. She wanted to leave immediately, and as host to my cousin a year older than me I had to succumb to her fit, and make her visit with us as pleasant as family elders may have wished.

While walking home on the same path we had taken—before my hopes for a nice afternoon had turned bitter and troublesome—the hurriedly consumed peas were turning a thousand rounds in my stomach. I was disturbed by her blunt, uneasy, and demanding behavior. A meter separated us on our walk, as I attempted to avoid looking at her white shoes and white socks. We reached home without exchanging a word, but our bitterness was not noticed; the adults were busy with their chatting and chores. Until, that is, Baghdo appeared unexpectedly around six, worry beaming from his bold and greasy forehead, and exposed my guest and me. At 5:30, he had gone to the cinema anticipating our exit (as he always did, and I would regularly emerge to find his big, happy smile). But on this day, I was not there; worried that I was lost with Sonia, he had rushed home to ask my parents if they knew our whereabouts. Disguising my disappointment with Sonia, I jumped to give him the news that I had rushed home since cousin wished to be in early, as her mother had piped into her ears repeatedly. Sonia and I never talked about her disturbing and unwelcoming behavior. We never told the imposing adults about the incident, and sat on it like a cold-blooded cobra encircled on itself, patiently waiting for new skin.

It was during this encounter, and because of Baghdo’s explanations, that my parents learned about my visits to Madame Lucy. As a result, I was forbidden from ever visiting the den again. Cousin Sonia had cost me my princely welcomes, my green peas, and the best circus offered by men and women, whose names I never got to know. At night Sonia refused to sleep; she’d get up for a drink of water, because she heard voices, to go to the bathroom, because of itchy mosquito bites (even though there were no mosquitos). She was a fish out of water, and if possible I would have taken one of two solutions: throw her in the sewer or grill her on the barbecue grid. For the rest of her stay, I neglected her and instead indulged in reading books. A few days later, Sonia and her Beirut attitude were sent back by train in the company of a distant relative. I kept making my secret visits to Baghdo until matters took a sudden change.

Not long after that, Madame Lucy passed away, sending a sad wave across Aleppo’s manly circles. Her precious first-choice girls were dispersed into unknown and questionable destinies, and her club became a legend and a part of Aleppo’s recent history. Her cabaret belonged to the age of elaborate Middle Eastern smoke-laden red-light houses for “romantic” excursions, where rich men showered belly dancers with paper money, shoving bills between large breasts or in ornate string garments hardly visible under bulging bellies. Where popped champagne bottles flowed on the floor and uncorked French wine dripped from their thorny moustaches and the vulgar red-painted stout lips of lost souls holding cigarettes to be lit. Where bundles of rolled, devalued Syrian pounds became giant match-sticks to light a ciggy. Where patrons heard intoxicated laughter, the sound of a drunken band, Lucy’s mad shouting at the girls who did not push enough alcohol, and her simultaneous gentle caresses on the patron’s back. And where there was vomit on the bathroom floor, spat spermatozoon under the tables, smashed old men trying to grip the shoulder of a disgusted companion, rubber plants in rubber pots (which, I learned much later, served as sinks for alcoholic beverages for women who did not want to get drunk), sudden visits by undercover agents, and taxis waiting like hunters in the night. It was all gone. My delicious green peas and sneaked previews were all silenced and put to rest, the curtains closed. Relegated to history before my eyes.

Unexpectedly, Madame Lucy’s flesh-heaven came alive once again, this time while I was living in Los Angeles—newly single after a pessoptmist divorce—right across the “Studio City Golf Course.” In my white-washed walls and beige wall-to-wall synthetic carpet, I was cooking black lentil soup with onions, minced spinach, lemon juice, cracked wheat, mint, cumin, salt, and red pepper powder when I heard the “tuk-tuk-tuk” on my plywood door. I rested the wooden ladle in the pot and rushed to the door, wiping my hands on the apron hanging loose from my neck. It was Harry, who had rushed ahead of me in getting a divorce; as misery loves company, we had become close friends. Harry was holding a book and grinning, signaling that there was something to be happy about in those dark days. It was Yerazayin Halebeh (Dreamy Aleppo) by Antranig Zarougian, whose earlier book “Men Without Childhood” was based on his own personal experience and depicted the life of Armenian survivors of the genocide who had grown up in Aleppo’s many orphanages. I had read it again and again, always thinking it would make a great film, better than “400 Blows,” “Madame Rosa,” “The Bicycle Thief,” and “Goodbye Children.” Like many others, this one remains un-read by booklovers and subsequently un-filmed for a diligent world audience.

“Hey, you should read this book, it is the Aleppo you talk about all the time,” Harry said, as he handed it to me and went to the kitchen to check the source of the aroma. “Your famous lentil soup again,” he said, and took a seat by the butcher block table that was a collective wedding gift from classmates from UCLA’s film school. The simmering soup was ready to be served, along with extra virgin olive oil from Spain, a sourdough baguette, feta cheese, and pickled cucumbers. With each hearty spoonful of soup, we consoled each other, compared notes, and agreed that we felt better by midnight when he left.

Seated in my half-broken armchair and barren, soulless ground-floor apartment with a broken window (sustained by a golf ball flung my way by an amateur golfer), I leafed through the book under the orange-shaded table lamp with an ice cold glass of vodka in my hand. I found myself engulfed in the pages, reading about a dreamy Aleppo of the 1940’s and 50s. The author wrote about his youth in the company of other newly minted young Armenian intellectuals and forthcoming leaders of the community, who frequented Madame Lucy’s love den, seeking pleasure and experience to formulate a manhood. Harry had just added another title on my impossible wish-list of books to be made into films. It made me remember the green peas and shaking naked legs, and I told myself that Madame Lucy’s cabaret was much better than Bob Fosse’s “Cabaret,” that the girls were healthier than Liza Minnelli and Marisa Berenson. Or Liliana Cavani’s “The Night Porter,” with Charlotte Rampling baring her 28-year-old breasts to the gaze of a maturing Dirk Bogart keeping her under house arrest. At Madame Lucy, the songs were better and the men were more real than the stiff German officers; yet, the socio-political atmosphere in 1960’s Syria and 1940’s Germany was almost the same. And I was grateful that I was able to escape from my house at nights and visit Baghdo, who worshiped me for lack of having his own child and easily tolerated my naughty nights.

Almost three decades later, I returned to Beirut and met cousin Sonia again. During our happy conversations over salt-roasted pumpkin seeds, we rehashed the old days and attempted to mend the gap of absent times and distance beyond a sea and ocean, between Beirut and Los Angeles. I asked her if she remembered going to Madame Lucy, to the Cinema Hamra to see “Lady in a Cage.” But she had wiped Aleppo from her brain. I think she had decided to forget her trip to Aleppo when she refused to hold my hand, making me suffer rejection for the first time.

I was taking out my wallet when Abu Omar, the Kurdish greengrocer of my neighborhood in Qantari, Beirut, handed me the black plastic bag filled with a kilo of fresh green peas, a large mountain of tomatoes, a few carrots, a couple of onions, and a garlic head.

—“4,500,” he said.

I paid him the equivalent of $3, said “shoukran” (thank you), and took the fresh earthly wealth.

— “Inshala nfrah mnak ya Baron” (God willing we may rejoice for you, Sir), he said meaning I should get married soon.

On my fourth-floor kitchen preparing the green pea stew, I thought about who to invite for dinner, debated making rice or bulgur pilaf, having red wine or something else? I stirred the pot with the long wooden spoon I had purchased in Tijuana, Mexico in 1983, and the aromatic steam rose, stirring my memory in response: And there was the 16-year-old Lucy in Beirut. Originally from Aleppo, she served as the very beautiful bait in the Israeli prostitution/spy ring of Madame Shulamit Arazi Cohen, which operated out of the Rambo Pub on Hamra St. until it was uncovered and she was arrested on Aug. 9, 1961. Lucy’s last name was Kupelian, like Baghdo’s, and I wondered if they had been separated by the genocide, or if she was related to any of the good Kupelians I had met later in life—Boghos, Roger, Gilda, Yervant, David, and the many others. Or if Shula was related to Elie Cohen, who was caught in Damascus in 1963 as an Israeli spy and whose hanging was broadcast live on my black-and-white TV. Or if she was related to any of the Cohens I had met in New York?

I tasted the fresh green peas to see if they had softened in the simmering and spicy tomato bath. With a pea smashed between my teeth, another Lucy unfolded in my mind’s eye: It was slightly before the 1994 Los Angeles earthquake, on a Saturday when I was routinely cooking and the TV was turned on to the Korean-owned channel that rented out airtime to immigrant TV programs. I heard the presenter of the Arabic program boasting a fresh video clip of a newly rising Egyptian belly dancer named Lucy Sarkissian. I found myself in front of the TV, with the wooden spoon in my hand, mesmerized, watching her almost-naked slim figure and round goods barely covered in green fishnet—in the color of Madame Lucy’s peas. Her dance was a perfect ballet exercise. She did not have the fat to throw about generously like a Madame Lucy girl. She was a technician to be watched, not a passion to be conquered. I made a mental note that the airborne fluffy green did not match well with her porcelain white skin and that, most of all, she did not have that peculiar detail of red-red liquid lips. She was in high heels, instead of exposing her bare feet and the silver bracelet on her ankle, which Middle Eastern men deemed as attractive as perfect breasts, shapely hips, slender arms, straight shoulders, a narrow waist, bedroom eyes, an adolescent nose, and that armful of a belly supported by powerful legs resting on smooth and well-rounded knee caps above grab-full calves. This Egyptian-Armenian Lucy indicated the change of times.

As time moves on—unnoticeably and unchangingly for a captain sailing the open seas—a decade had passed since I had seen Lucy dance on my TV screen, and my friend Karim and I were digging deep into our green pea stew in Al Fulfula restaurant, near the famed Yacoubian building in Al Tahrir Square in downtown Cairo. I inquired about the Lucy of his turf. “She was a celebrity,” he said, “until her departure to Los Angeles hoping to cause an earthquake with her clean Westernized method. Instead she vanished into oblivion with the hot wasteland winds blown from the Dead Valley to the islands of Hawaii.”

The stew was done. I turned off the gas and tasted a spoonful for a spice adjustment and final decision, while still deciding who to invite over to avoid a lonely meal. Unaware that my bowl was filled, I indulged myself in the green pea stew I qualified it to be less than my mother’s and slightly more than Madame Lucy’s.

Dear Nigol,

With some unexpected interruptions finally I managed to

finish this wonderful memoir.

Thank you.

Dear Mr. Bezjian:

Thank you for sharing another fascinating, delicious story. The name “kupelian” brings back fond memories, as well as the smell of the fresh “menfoush” and the pumpkin seeds…

A wonderful article, realy enjoyed reading it. How can one get hold of Antranig Zarougian’s books? They are not available on Amazon… Can someone advise?

Thank you dear, for Zaougian’s book you can try Abril or Sardarabad books stre in LA, Ca.

Thank you for this beautiful memoir of time not so long ago from a place that has changed too much.

Well done.

Mark

Parev Nigol jan. thank you for bringing back memories of Haleb.Torontoyen sarkatz vospe abourin hodere ge pooren …….icnbes yerp foolgi Abdoyin khanutin archeven gancneyink.

Togh Dere kizi mishd ouj da te grnas aybes mish hedakerkir badmoutyuner horines ..

Abris Nigolaye Voski… Husam shoudov ge desnving yev Jidedye gertank … Vicken