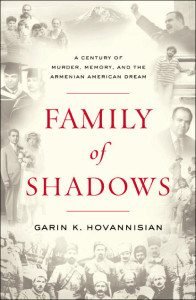

The following excerpt is adapted from Garin K. Hovannisian’s memoir, Family of Shadows: A Century of Murder, Memory, and the Armenian American Dream, which HarperCollins will release on Sept. 21. For more information, visit www.familyofshadows.com.

By the fall of 1974, a president had resigned in Washington and a governor in Sacramento had decided, very curiously, to pass up a third term. But to Raffi K. Hovannisian, student councilman and freshman football star at Palisades High School in Los Angeles, the events of his world seemed not to matter anymore. For on one September afternoon, Raffi had been cast into his first meeting of the Armenian Youth Federation (AYF)—a group of 20 boys and girls in the San Fernando Valley of California, who were about to begin a secret mission in a foreign land.

Raffi was a natural leader, which is not to say that he strived for power—that, in his turn, he did—but to say that he achieved power quite without trying. The depth of his voice, the mysterious sense of his national purpose—the very qualities that helped him navigate the social labyrinth of Pali High—also distinguished him in the AYF. He was elected vice-president, and then president, of the San Fernando Valley chapter.

Before he knew it, Raffi was at the center of a brotherhood known as “the pals”—with Armen, Hrair, Raffi, Greg, Moushig, Khajag, Armen, Ara, Steve, Garo, and Kevo. After the week’s AYF meeting, the boys would sit around greasy tables at diners and fast-food joints and speak of Armenia together. “The important thing is this: To be able at any moment to sacrifice what we are for what we could become.” These words, printed in an AYF pamphlet, referred to the idea of veratarts, the return of a new generation of Diasporan Armenians to a free, independent, and united homeland.

Raffi was already preparing for that return, and in a big way. When asked about his career plans, he was quick to respond: “president of Armenia.” Raffi could have said “president of the United States”—at least there was such a title. But Armenia had no president. Its west had been obliterated in genocide, the east of it tyrannized and absorbed into the Soviet Union. And so Armenia was not free, not independent, not united: not real.

It could be too easy to forget, caught up in the conversations of a national destiny, that the pals were American teenagers who were not unmoved by the tides of youth. Very often, after midnight, the boys would crawl out of their beds, jump out of their windows, climb into cars, and race to the beaches of the Pacific Ocean. A few AYF girls would join them there. The crackle of a campfire, the clank of bottles, and soon the boys and girls would be singing under the stars.

When possible, Raffi would convert the music hits of the day into alternative Armenian national anthems. Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” became, by moonlight, “Sweet Home Armenia.” The lyrics of Bread’s love ballad “I would give everything I own just to have you back again” Raffi sang not to a woman but to the memory of a free homeland. And John Denver’s hit song “Country Roads” evolved into a masterpiece of Armenian nationalism:

Country roads, take me home

To the place I belong—

West Armenia, mountain mama,

Take me home, country roads.

They stripped down to their underwear and broke into the surf. The waves were cold and powerful, and the boys dove into the darkness. They swam deeper and deeper, testing their fears that they might conquer them. When they returned to land, they played a drinking game called Thumper and then a game of physical endurance called esheg, or donkey, which had traveled generations from homeland to oceanfront. As the girls looked on, one of the boys was blindfolded. His friends hovered around him, and he waited for the moment when someone would thrash him on the head. He would absorb the pain, take off the blindfold, and try to identify the assailant. Only if he did this successfully could he rejoin the boisterous crowd.

The beach was friendship. The beach was love. The beach was a training camp for national commitment. At the beach, the boys were invincible. They felt that together they could kick anyone’s ass, that they could avenge the rape and murder of their grandmothers. They were keeping each other strong, keeping each other Armenian. Raffi was keeping his generation faithful to the possibility of a miracle—a chance opening in history. He said to them and they said to him again and again:

“If Armenia becomes free and independent, I will move there.”

They said it all through the night—an oath before an ocean—but the boys could not foresee that soon, sooner than they thought, they would be called to account for their words. It would be more difficult than they had imagined, but one of them, at least, knew that he could do it. He had been born here, yes. His father had been born here. But somehow Raffi Hovannisian knew that none of this—not the ocean and not the football field—was actually his.

Armenia need more guys like Raffi Hovannisian. We all be proud to have Raffi.

God bless you Raffi