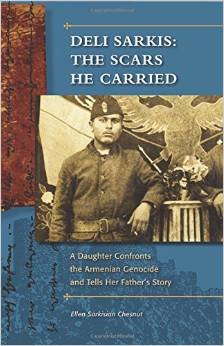

Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried: A Daughter Confronts the Armenian Genocide and Tells Her Father’s Story

By Ellen Sarkisian Chestnut

Two Harbors Press, Minneapolis, Minn., 2014

186 pp., with family photographs and bibliography of sources

Book review by Rubina Peroomian, Ph.D.

With a first glance, I knew that my interest in Deli Sarkis lies not only in the memoir of a survivor of the Armenian Genocide—a major theme in my studies and research—but also in the responses of the offspring, the second-generation survivors of the genocide, to their parents’ traumatic past. And this topic happens to be at the core of my present undertaking.

So the story of another torturous life and miraculous survival with permanent scars, physical and psychological, unfolds. Sarkis, a native of Keramet village on the shores of Lake Iznik in the Bursa Province of Turkey, describes his horrifying experience during the deportations and massacres. This is on behest of his oldest daughter, Shakeh/Ellen, when he is old and frail. Fearing that he will pass with his story untold, she prompts him to recount his memoirs while she takes notes. She transcribes the notes taken since 1988 and receives her father’s approval in 1995.

It all started on Oct. 29, 1915, when a messenger on horseback brought the alarming news. Armenians had two days to prepare for a journey by train, and that was “for their own safety.” The panicked and fear-stricken Armenians knew the meaning of that unknown trek. Rumors of the sort happening to Armenians all over the Ottoman Empire had been going around for some time. It was their turn now. Sarkis was 10 years old. The caravan of 1,500 men, women, and children, the entire Armenian population of Keramet, began to move on foot or on ox-driven carts toward Mekece train station 30 miles away. The cattle cars would take them to Adana from where they were ordered to walk. And the ghastly scenes of unimaginable atrocities follow, as Sarkis describes in detail their passage to Raqqa, Deir-al-Zor, Ras-al-Ain, to the outskirts of Mosul. The caravan was gradually dissipated. Sarkis was left with her mother. His father and siblings had succumbed to the hardship of the road. The two of them, homeless in the streets of Mosul, begged for food during the day, and at night slept in the street next to a building. One day, Sarkis came back from his “scavenging mission” to find his mother dead. He was left alone, an orphan boy wandering from one place to another, suffering from hunger and from trachoma, always in fear of being killed if caught. He found one of his brothers working as a slave at the home of a wealthy Arab. The Arab agreed to take him, too. After the war was over, the AGBU founded an orphanage in Mosul. Sarkis left the Arab’s home and went to the orphanage, where he stayed six months with cherished memories of his caretakers and teachers there.

Sarkis’s ordeal continued, out of the orphanage to Constantinople and back to Keramet in 1919. He wanted to see what had happened to his paternal home. What he found was excruciating. The house was stripped to the bare walls. In the dust-covered bedroom where his parents had slept, he “found a couple of strands of longue brown hair. Could they be my mother’s, I wondered? I sat up and ran my fingers along the strands and caressed them. … This was all that was left of my mother besides my undying memories of her. I started to sob.” There was no way a few returning survivors could revive the village. There was lawlessness. Thieves and murderers controlled the roads. “Young boys…were especially vulnerable to kidnapping, torture, rape, and brutal murder.” Keramet was not safe. Sarkis decided to move on, become a Greek soldier, and fight. After serving in the Greek army for a year-and-a half, he was discharged. He soon found himself under fire from an approaching Turkish army in Manisa and then in Smyrna. He was a witness and a survivor of the Smyrna fire. He was once almost executed by Turkish soldiers. When asked later which experience had been worse—“the massacres and deportations into the wasteland of Syria, or the burning and destruction of the population and the city of Smyrna”—“[w]ithout hesitation, I would have to say Smyrna,” he said. “I don’t think anyone can imagine the heartrending scenes that I witnessed.”

To complement the account of the situation, Ellen brings in the memoirs of Hagop Nigoghossian, another Kerametsi. It is in his memoirs that we read about acts of retaliation by a band of young Armenian men. They attacked the neighboring Turkish village, took some 40 men hostage, and killed some of them. These Armenians were full of rage and revenge. They were avenging the murder of their parents, their wife and children, the destruction of the whole nation. “They had nothing to lose because they had already lost everything.” That was in September 1919. But ironically, the Turkish denialists use these incidents to substantiate their claim: It was war time, and both sides killed each other. Or, people died on both sides as the Ottoman Empire was disintegrating. Chronology and sequence of events is grossly disregarded.

The rest of Sarkis’s story covers his passage to Greece, then Bulgaria and to France with a Nansenian passport, and back to post-war Iraq. He mostly lived in Mosul, where he married Ellen’s mother in 1938. Sarkis went from one job to another, with no specific job-training or skill, until the family migrated to the U.S. in 1941 and settled in San Francisco.

A typical life of newcomers to the U.S. with ups and downs, with difficulties to overcome the everyday challenges of the New World, followed. Sarkis is caught in that whirlpool of challenges and responsibilities to provide for his wife and four children. And alcohol was the remedy lightening his soul and the heavy burden of life he was unable to bear. He was physically scarred on his head and his leg. He was indeed the embodiment of the Turkish moniker “leftovers of the sword,” which referred to Armenians who undeservedly survived. And he was psychologically scarred. He tried to remain in control of his temper, but when somehow he was reminded of the Turkish atrocities, he could not refrain. “Suppressed memories jump out at the strangest times,” Ellen surmises.

What particularly interested me in this book, as I mentioned in the beginning, was Ellen’s own interjections in response to the Turkish atrocities and the fate befallen to her family and her nation. Sarkis’s life story is packed between two testimonies by Ellen Sarkisian Chestnut. The first is the account of her pilgrimage in 2009 to the places Sarkis’s father and mother had lived and passed as refugees through Turkey. She needed to understand and build a physical and historical context for her father’s story. She had gone out of her way to bring in the historical facts, to collect information about the village, the people, the victims and their experience. This first testimony comes as an introductory historical survey, but what differentiates it from others accompanying similar memoirs is that she associates each historical fact, event, or place with a parent’s or a relative’s personal experience of involvement with it.

The second is her contemplation of life as a second-generation survivor of the Armenian Genocide, living with parents who were anything but normal compared to the easygoing American families she knew. Looking back at her upbringing, she could clearly see the impact of the ordeal her parents had experienced during the massacres and deportations. “When we were growing up, his rages would come and go. Sometimes he would be so understanding and speak so softly and sweetly, like the father we always dreamed about. At other times he would be critical of us all and beside himself with anger. I tried to understand but could never discover the reason for this split-personality.” Ellen’s parents loved their children but never showed them affection, “very little as we grew older, when we could have used them. … If both Father and Mother had been more outgoing with affection and had not kept all their good thoughts about us to themselves. … I think, life would have been so much easier for all of us growing up,” Ellen thinks in retrospect. One time their father had told them, “I love you kids very much,” and the children “were struck dumb and very surprised.” No emotional support, no expression of pride about their children’s achievements. Ellen tries to find the reason, and attributes this behavior to superstition and believing in evil eye. That is, of course, true, but there is also the trauma of orphanhood and homelessness, and a difficult battle to survive that forced her father to play tough, with no unnecessary emotions. How could Ellen or her siblings understand and accept this when they were growing up? Sarkis was known as a tough and rough guy in his youth in Mosul. That must have been the reason why they called him Deli (Crazy).

The most dramatic crash between the two generations occurred with her younger sister Janet. She was an artist, a free soul, the more acculturated one in the family. It was the mid-1960’s in America, and the trend to move out and live free without constraints, make artistic experimentations, and use recreational drugs, was the ideal of youth drawn in the Hippie movement, especially in the Bay Area. This happened to many Armenian families in that period of time. But if the parents were not emigrants with a burden of culture and traditions frin the Old World, if they were a little more permissive toward the New World ways and allowed the lifestyle to creep into their family, could they prevent the breaking of moral order and family life? Janet had a turbulent life. She lived with her American boyfriend, who betrayed her along the way, and she returned to her family with broken wings. By the late 1960’s, the three of them, except for the youngest sister, Lucy, had moved out. Father’s alcoholism and mother’s stressful life that led to her heart attack and eventual death was Lucy’s to bear.

Deli Sarkis passed away on April 19, 1995, years after his beloved wife, Evelin, and days before the 80th anniversary of the genocide. He died lonely and miles away from his birthplace Keramet. But he died peacefully, at least knowing that “A long time ago, we had forgiven him for the difficulties of growing up with such a wounded, but at the same time such a vibrant and charismatic human being.” And so the narrative ends with a pledge by Ellen and her sister Lucy to keep their father forever in their hearts, “and his story, along with that of our beloved relatives and the villagers of Keramet, would be with us also.”

Deli Sarkis: The Scars He Carried, with all the details of events, places, and people that the author provides, is a valuable contribution to the study of the Armenian Genocide. It is a voice added to the thousands, testifying to a crime against humanity that was committed with impunity. I highly recommend this book not only to the general public, but also as a reading material for high school students in their human rights and history courses. The author, as a teacher all her life, has a way of communicating, attracting, and motivating. The book needs closer proofreading, perhaps in the next edition, but it certainly is a good read.

I liked your fathers story, as a matter of fact my father’s life story almost is the same as are all survivors stories. He had suffered three axe scars on his skull.

He had written his memoires in Armenian. Recently we translated his book from Armenian to English, soon it’s going to be printed and published.

I’ll bet Zoryan Institute has many similar stories that, like Sarkis’, are too important to go unrecognized, like my father’s that they documented. They go little good to sit unexplored…