‘We want to believe in the victory of Freedom and of tomorrow’s brotherhood, we want to enjoy smiles, we want to strengthen our faith that famine is not eternal, blood is not eternal, yeghern is not eternal.’

E. Aknuni (1910)1

The meaning of yeghern in Classical Armenian (“evil,” “crime,” and “calamity”) may seem to give some credence to claims that Medz Yeghern doesindeed mean “Great Calamity.” However, before we accept these claims, we must first verify whether those three meanings have survived in Modern Armenian. Their survival is contingent not only on their presence in dictionaries, but also on their actual usagein literature. As translators know firsthand, dictionaries may give definitions, but the key to using them effectively depends on one’s ability to place a given literal definition within its proper context.

In this study, we will first overview the definitions of yeghern in Modern Armenian dictionaries, both monolingual and multilingual, published before and after 1915, to validate the accuracy of the “Great Calamity” translation.

The meaning of ‘yeghern’ in Modern Armenian until 1915

A primary meaning of yeghern as a breach of law or a crime was already present in Modern Armenian before 1769. Proof is offered by the second tome of the Haigazian Dictionary by Mekhitar of Sebastia and his disciples, published that year. This dictionary contained three wordlists: a Classical Armenian dictionary, “where the words of the Haigazian [Classical] language are interpreted only with vernacular [ashkharhabar] or Turkish words”; a Modern Armenian dictionary with translations into Classical Armenian; and a dictionary of proper names. In the second volume, the word yeghern appeared interpreted in the “vernacular language” as մեծ անօրէնութիւն [medz anorenutiun, “great lawlessness”], անիրաւութիւն [aniravutiun, “evil”].2 This suggests thatatsome time between the 5th century and 1769, yeghern was no longer defined as “calamity.”

This development was reflected in the 1821 English-Armenian dictionary of Rev. Paschal Aucher and John Brand, which introduced yeghern as one of the translations for the English words “crime”and “evil”: crime = յանցանք [hantsank], մեղք [meghk], վնաս [vnas], չարիք [charik], եղեռն [yeghern], ոճիր [vojir]; evil = չարիք [charik], յանցանք [hantsank], եղեռն [yeghern], վնաս [vnas], անիրաւութիւն [aniravutiun], զրկանք [zrgank], չարութիւն [charutiun], ապականութիւն [abaganutiun], վատթարութիւն [vadtarutiun], աղէտք [aghedk], թշուառութիւն [tshvarutiun], դառնութիւն [tarnutiun], ախտ [akhd], հիւանդութիւն [hivantutiun]. The word was not listed as translation for calamity, catastrophe, or disaster: calamity = թշուառութիւն [tshvarutiun], աղէտք [aghedk], վիշտ [vishd], չարիք [charik]; catastrophe = յեղափոխութիւն [heghapokhutiun], ելք աղէտալի [yelk aghedali], կատարած ողբալի [gadaradz voghpali]; disaster = դժբախտութիւն [tzhpakhdutiun], աղէտք [aghedk], չարիք [charik], վիշտք [vishdk], տառապանք [darabank], ձախորդութիւն [tzhakhortutiun].3

The Armenian-English dictionary of 1825 by the same pair repeated the trend. The meanings for yeghern reflected “crime” and “evil”: եղեռն = rascality, offence, misdeed, malice, crime, wickedness.4

Interestingly, the revision of this dictionary, undertaken by Rev. Matthias Bedrossian and published in 1879, added “catastrophe” as a secondary meaning for yeghern.5 It goes without saying that he wished to accommodate the classical meaning of yeghern, just as Rev. Srabion Eminian had done in his 1851 French-Armenian-Turkish dictionary, where he translated yeghern into French as mal (“evil”) and calamité (“calamity”). Incidentally, this was the reason the dictionary also contained the only available translation of yeghern into Turkish as felâket.6 However, it is interesting to note that in 1893, Gomidas Voskian’s French-Armenian dictionary wrote: “yeghern = see vojir,” and “vojir = crime, attentat [attack], méfait [wrongdoing], forfeit [crime].”7The fact that yeghern did not appear as translation of “catastrophe,” “calamity,” or “disaster” in late 19th-century and early 20th-century English-Armenian dictionaries shows that the meaning was completely outdated by that point in time: crime = եղեռն [yeghern], ոճիր [vojir] (V. H. Hagopian, 1907); crime = յանցանք [hantsank], եղեռն [yeghern], ոճիր [vojir] (M. K. Minassian, 1907); crime = ոճիր [vojir], եղեռնագործութիւն [yeghernakordzutiun], մեծ անիրաւութիւն [medz aniravutiun] (Z. D. S. Papazian, 1910).8

The use of ‘yeghern’ at the time of the Massacre of Adana

The word appeared in literary usage, indeed. For instance, it showed up twice in Avetik Isahakian’s famous philosophical narrative poem, “Abu-Lala Mahari,”written in 1909 and published in 1911. Its protagonist, the homonymous Arab poet, expresses his contempt and pessimism for humanity. The two relevant stanzas follow:

And woman I hate. She’s the fertile cause of unbridled crime [yeghern], of passion the seed;

A well never failing, whose copiousness steams earth’s growing wickedness water and feed.

For nothing but gain. To the claw of crime [yeghern]divinity men will ascribe;

Such ever is man, the image of God—whom abort of the devil would best describe.9

Isahakian’s poem was written in the same year of the forerunner to the Armenian Genocide: the 1909 massacres of Adana. E. Aknuni, one of the leaders of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF) in the early 20th century, was nevertheless hopeful that better times were to come. In September 1910, when touring the United States, he wrote an essay titled “To the Exiled Armenians of America,” in which he inscribed the words of the epigraph: “… [W]e want to strengthen our faith that famine is not eternal, bloodletting is not eternal, yeghern is not eternal.”

Logical thinking in the process of writing would have placed one reference to a natural cause of death (“calamity”) along the other (“famine”). The order of Aknuni’s references indicates that yeghern did not mean “calamity,” but “crime,” which is why he placed it after a violent cause of death (“bloodletting”).

Around the same time, Armenian writer Tlgadintsi (Hovhannes Harutiunian, 1860-1915) published a chronicle called “Take My Sun, Send Me My Death,” where his interlocutor, Rev. Aslanian, a priest who had been to Adana, was quoted as saying: “Babikian too, that poor man but also a select and true Armenian, was melting like a candle against the fire when he saw things and heard the stories of the unprecedented extremes of the yeghern committed by the Turkish mob with a kind of official treason.”10

The reader would have readily understood yeghern to mean something committed by man (a crime), rather than by nature (a calamity), supported by Simon Kapamajian’s 1910 modern Armenian dictionary, which defined yeghern as “քաղաքական կամ բարոյական օրէնքի դրժում [breach of political or moral law]; չարիք [evil]; վնաս [harm]; ոճիր [crime].”11

Hagop Babikian (1856-1909), an Ittihad Party deputy in the Ottoman Parliament, had been sent to Adana as part of an investigative commission. He died under suspicious circumstances only two days after having shown a draft of his damning report to some parliament members. His report was surreptitiously published in Ottoman-Turkish in Constantinople in 1913. It is likely that it was translated into Armenian at the time, but only published six years later due to political turmoil and the genocide years. Hagop Sarkisian’s translation was titled “The Yeghern ofAdana.” In his preface, dated Feb. 1, 1919, he made clear that “[Babikian] was poisoned by the Young Turks as repayment for this report about the yeghern of Adana, which he prepared for the Chamber of Deputies and for which he died on July 20, 1909.” The preface began with the following statement:

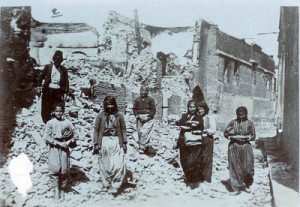

“It was in the spring of 1909 when the black Mongolian claw painted the whole Cilician plain red and turned it into one vast cemetery; the rivers Sihoun [Seyhan] and Jihoun [Ceyhan] received floods of Armenian blood. The Young Turks, openly or secretly, rubbed their hands together with devilish smiles on their faces and with an insolence worthy of hyenas at having accomplished some supreme duty spat in the face of Civilization and of the Allah they worshipped. This was the result of the old and new Turkish mentality, one which never wanted to understand that the owners of this country, of yesterday and of tomorrow, might have the right to live too. The days of awakening came, nevertheless; it was necessary to sow ashes over the Medz Yeghern and conduct the burial of Justice crucified.”12

While Babikian’s use of yeghern by itselfmay not have shed a great deal of light on its meaning, the context surrounding the words Medz Yeghern—from the “black Mongolian claw” to “Justice crucified”—make it quite clear that there was no question of “calamity,” or natural disaster, here. The massacres of Adana had turned yeghern from “crime,” into “pogrom.”

It is curious that the translator, writing in 1919, used the concept of Medz Yeghern, butdid not make any explicit reference to the events of 1915-18. He was in fact echoing an expression already used by Sahag II Khabayan, Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia, in a letter of appreciation written on Dec. 4, 1912 and printed in “The Catastrophe [Aghed] of Cilicia,” by Hagop Terzian, a witness to the massacre of Adana. The letter stated the following in its penultimate sentence:

“It [the book] is the living image of the Medz Yeghern, extracted from beneath the ruins and the ashes by the dedicated and inquisitive effort of an authentic child of Cilicia, which will be the eternal affront of the much-touted civilization and the inexistent humanism of the 20th century.” 13

The horror of Cilicia, where Armenians young and old had been indiscriminately slaughtered, surpassed the massacres of 1895-96 in both scope and brutality: “… [T]he most painful and hellish episodes of the events of ’95, in comparison with what actually happened in Kozluk, were not even the beatings sparked by the ballgames of schoolboys…”14 The Catholicos bore witness to the annihilation of his flock three years later in a much bigger “eternal affront” that also took the lives of Aknuni and Tlgadintsi, and was condemned by the Allied Powers (Great Britain, France, and Russia), as early as May 24, 1915, as the “new crimes of Turkey against humanity and civilization,” as reported by the U.S. State Department.15

Guy de Lusignan’s and K. J. Basmadjian’s Armenian-French abridged dictionary, ironically published in 1915, defined yeghern as “crime, forfait [crime], attentat [attack], délit [wrongdoing]; malheur [misfortune], fatalité [fatality], catastrophe.”16 A single dictionary that has the secondary meaning of yeghern defined as “catastrophe” cannot prove that such an understanding was so widespread that Armenians named the darkest page of their history to imply that meaning.

The reason for this intriguing double meaning was that Karapet Basmadjian had posthumously abridged Lusignan’s voluminous dictionary, which revised his 1861 Armenian-French dictionary. The definition of two groups (“crime” and “misfortune”) repeated the latter; Lusignan had followed the inaccurate classification of the New Haigazian Dictionary and put together yeghern (եղեռն) and yegher (եղեր) as synonymous words. Thus, he defined yeghern as “crime, forfait [crime], attentat [attack], délit [wrongdoing]; malheur [misfortune], fatalité [fatality], catastrophe.”17

Interestingly, Lusignan’s voluminous French-Armenian dictionary, published in 1900, defined crime as follows: “ոճիր [vojir], եղեռն [yeghern], ոճրագործութիւն [vojrakordzutiun], եղեռնագործութիւն [yeghernakordzutiun], ժանտագործութիւն [zhandakordzutiun], վրիժագործութիւն [vrizhakordzutiun], անօրէնութիւն [anorenutiun], ապիրատութիւն [abiradutiun],” with the phrase commettre un crime (“to commit a crime”) translated as ոճիր, եղեռն գործել [vojir, yeghern kordzel]. The sixth meaning of the word mal (“evil”) was “չար [char], անպատեհութիւն [anbadehutiun], եղեռն [yeghern], մեղ [megh], վնաս [vnas], ապիրատութիւն [abiradutiun].”But the Armenian equivalents for calamité (“աղէտք [aghedk]; տառապանք [darabank], խարուանք [kharvank], փորձանք [portzank]”), catastrophe (“արկած [argadz], աղէտք [aghedk], չարաղէտ դէպք [charaghed tebk], մեծ չարիք [medz charik]”) and désastre (“աղէտք [aghedk], թշուառութիւն [tshvarutiun]”) did not contain any trace of yeghern.18

Before 1915, then, yeghern was solidly established, both in dictionaries and in literary texts, with the meaning of “crime.” The genocide would bring the use of the word to a higher level.

Notes

[1] E. Aknuni, Depi Yerkir (Towards the Country), Boston: Hairenik Press, 1911, p. 15.

2 Bargirk haykazian lezvi (Dictionary of the Armenian Language), vol. 2, Venice: Antoni Bortoli, 1769, p. 113.

3 Father Paschal Aucher and John Brand, A Dictionary English and Armenian, Venice: Armenian Academy of S. Lazarus, 1821p. 116, 128, 213, 258, 318.

4 John Brand and Father Paschal Aucher, A Dictionary Armenian and English, Venice: Armenian Academy of S. Lazarus, 1825, p. 180.

5 Rev. Matthias Bedrossian, New Dictionary Armenian-English, Venice: St. Lazarus, 1875-1879, p. 155.

6 Rev. Srabion Eminian, Baragirk gagghieren-hayeren-tajkeren (French-Armenian-Turkish Dictionary), Vienna: Mekhitarist Press, 1871, p. 155, 743 (first edition, 1851).

7 Gomidas A. Voskian, Ardzern baragirk hayeren gagghieren (Armenian-French Pocket Dictionary), Constantinople: H. Matteosian, 1893, p. 195, 641.

8 V. H. Hagopian, A Dictionary English-Armenian, Constantinople: H. Matteosian, 1907, p. 159; M. K. Minassian, A Dictionary, English, Armemian and Armeno-Turkish, Constantinople: V. and H. Der Nersessian, 1908, p. 246; Z. D. S. Papazian, Illustrated Practical Dictionary English-Armenian, Constantinople: H. Matteosian, 1910, p. 252.

9 See the original Armenian in Avetik Isahakian, Yerker (Works), Yerevan: Sovetakan Grogh, 1987, p. 237, 250. The first stanza is a literal reproduction of Zabelle C. Boyajian’s 1948 translation, while the second revises the translation, where the word yeghern had not been translated (“For nothing but gain. To the grabbing claw honour and sanctity men will ascribe;/ Such ever is man, ‘the Image of God’—whom ‘Sons of the Devil’ would best describe”). For the two stanzas in Boyajian’s translation, seeAvetik Isakakian: Great Armenian Poet, Armenian Program, 35th Annual Women’s International Exposition, November 3-9, 1958, 71st Regiment Armory, Park Ave. at 34th St., New York City, p. 11 and 18.

10 Tlgadintsin yev ir gortze (Tlgadintsi and His Work), Boston: Tulgadintzi Alumni Union, 1927, p. 230.

11 Simon Kapamajian, Nor baragirk hayeren lezvi (New Dictionary of the Armenian Language), Constantinople: R. Sakayan Press, 1910, p. 407.

12 Hagop Babikian, Atanayi yegherne (The Yeghern of Adana), translated by Hagop Sarkisian, Aleppo: Armenian Prelacy of Aleppo, 2009, p. 15-16 (second edition).

13 Hishatakaran Atanayi agheti (Memorial of the Catastrophe of Cilicia), vol. II, Antelias: Collection of the 100th Anniversary of the Massacre of Adana, 2010, p. 14 (third edition of Terzian’s book).

14 Tlgadintsin yev ir gortze, p. 229.

15 Annette Höss, “The Trial of Perpetrators by the Turkish Military Tribunals: The Case of Yozgat,” in Richard Hovannisian (ed.), The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1992, p. 209.

16 Guy de Lusignan-K. J. Basmadjian, Dictionnaire portatif armenien moderne français, Constantinople: Librairie B. Balentz – Imprimerie O. Arzouman, 1915, p. 199.

17 G. A. Nar-Bey de Lusignan, Dictionnaire arménien- français and français-arménien, third edition, Paris: L. Hachette and Co., 1881, p. 239.

18 Guy de Lusignan, Nouveau dictionnaire illustré français-arménien, vol. I, Constantinople: H. Matteosian, 1910, p. 358, 408, 626, 710; vol. II, p. 138.

Vartan Matiossian has presented an in-depth, informative and very interesting study of the evolution of the word Yeghern.

Few years ago there was a German made documentary titled Aghed. I naturally understood what the word meant and implied but it sounded alien to me to ascribe to the 1915 Armenian Experience. Therein lies the subtle but profound influence of culture on the use of a word even among the users of the ‘same” language, let alone in attempting to translate.

The pre-1965 commemoration of the Armenian Genocide was much more different than what it has evolved to since then. It was more of a lamenting, grieving indoors with the Avedis Aharanian’s famed quote plastered on the wall. Yeghern was the word used then and not tseghaspanoutiun- genocide – as much. My formative years were shaped there.

In the end, I believe, its not word that constricts its evolution it’s the users who may expand on its use. Yeghern may have had different meanings at one time. However, as far as I am concerned the post 1915 use of the capitalized word Yeghern strictly defined the 1915 Armenian experience that altered our millennia old history forever.

It is time for us to coin our Word, much like the word holocaust has now come to define the WWII Jewish experience. Incidentally Winston Churchill has used the word holocaust to characterize the Armenian experience. But that is now history.

The use of the word genocide is being trivialized. I say this neither out of disrespect nor out of being insensitive to the massive killings that have been going on but because of the liberal use of the word genocide especially within the context of its political ramification and also to distinguish what happened to us in 1915. Ours is tragically unique. I quoted Raffi Hovanissian. The interested reader may read the comment I made to Vartan’s preceding article regarding the word Yeghern.

Yeghern is very much established in our, at least in Western Armenian usage, to mean the 1915 happening. It is time that we adopt and capitalize our own unique Word, it may be the Latinized use of the word Yeghern or the use of the capitalized Calamity. My choice is for the latter, The Calamity.

No offense, but have you actually been reading Matiossian’s articles? If so, can you explain why and how you arrive at the translation ‘Calamity’ for Yeghern, since the whole focus of his articles has been that this translation is fundamentally wrong?

Vahe, I disagree; ‘The Calamity’ doesn’t capture the intentional nature of the genocidal campaign of the CUP. It was a calamity to be sure, but call it what it was: The Armenian Genocide.

Boyajian, you are absolutely right. The English word calamity is devoid of the intentional nature of things. Your objection is valid and is well understood.

The word crime in English language does not adequately describe Yeghern in Armenian, as far as I am concerned. In Armenian we say one committed a crime – vojer kordsets. I have no recollection of ever reading in Armenian that one committed a Yeghern.

A Yeghern in Armenian, as I have understood it to be, is a happening, a calamity, a disaster of immense proportion that comes out of nowhere and destroys everything in its path causing much anguish. Another word for Yeghern in Armenian in Aghed, which I think is more used in Eastern Armenian usage than Western.

In true sense the English word calamity will never be a true substitute for the Armenian word Yeghern. However, I know no other appropriate alternative in English.

Vahe, thanks for your explanation. Since we are looking for a unique name to associate with our calamity, and since calamity doesn’t quite convey the full impact of that event, how about ‘The Blood-letting’ or ‘The Great Killing.’ Or better yet, how about ‘The Armenian Genocide.’ Seriously, why must we try so hard for a label when the right one already exists?

“It is time for us to coin our Word, much like the word holocaust has now come to define the WWII Jewish experience. Incidentally Winston Churchill has used the word holocaust to characterize the Armenian experience. But that is now history.”

Robert Fisk, a leading Middle East historian, routinely refers to the Armenian Genocide as a holocaust. In his international bestseller The Great War for Civilisation: the conquest of the Middle East, Harper Perennial, 2006, you will find that Chapter 10 is headed; The First Holocaust. Facing this title page is a map showing the principal routes of deportation, the centers of massacre, etc. The map is titled; The 1915 Armenian Genocide in the Turkish Empire. Here is an excerpt found on p. 390: “The Turks brought whole families up here to kill them. It went on for days. They would tie them together in lines, men, children, women, most of them starving and sick, many naked. Then they would push them off the hill into the river and shoot one of them. The dead body would then carry the others down and drown them. It was cheap that way. It cost only one bullet.”

Here is an excerpt from P. 391; “The soldiers then came and in front of the mothers, they picked up each child – maybe the child was six or seven or eight – and they threw them up in the air and let them drop on the old stones. If they survived, the Turkish soldiers picked them up again by their feet and beat their brains out on the stones.”

This does not sound like a “calamity” to me. It sounds like Genocide. Robert Fisk has got it right; what was done to us is called the Armenian Genocide. On page 414, Fisk writes; “It was a Polish-born Jew, Raphael Lemkin, who in 1944 invented the word ‘genocide’ for the Armenians, an act which helped to put in place the legal and moral basis for a culture of human rights.”

Not only does Robert Fisk have it right, but so did Raphael Lemkin. What was done to the Armenians in 1915 is called the Armenian Genocide. Everything else is meaningless chatter.

Perouz

Churchill has used the word holocaust in its descriptive form: “Destruction or slaughter on a mass scale, esp. caused by fire or nuclear war: a nuclear holocaust” (Wikipedia.

Robert Fisk has used the capitalized word meaning “The mass murder of Jews under the German Nazi regime during the period 1941–45.” (Wikipedia).

I think whenever one comes across the word holocaust, even if not capitalized, a mental connection to the extermination of the Jews is usually made.

In advocating using the word Calamity for Yeghern as uniquely descriptive word for the Armenian Genocide, akin to holocaust, I never meant to belittle the use of the word Genocide, of course. However, I did not consider the matter to be a meaningless chatter given the unique place of the word Yeghern in the post 1915 Armenian literature.

The word – Yeghern- served to echo sentiments of the many apparently because the word tseghspanoutiun would not.

The Turkish massacre of the Armenians started in 1877, after the Ottoman Empire lost a war with Russia. It went on further, when the Balkan peoples rebelled and got their independence from the Ottoman Empire, with Russian help. This is what led to the Young Turk Party to have a party meeting in Salonika in 1911. Where it was not to be massacres like what happened from 1894 to 1896, and 1909, but forced marches out into the Syrian and Mesopotamian deserts, while under the cover of World War I. No different than Nazi Germany’s Final Solution under the cover of World War II.

Yessss,

The very event of genocide had foot prints of violance by Ottomans behind it. The Hamidian massecars of 1896 was one.

The Turks not only lost against Christian Bulkans and Russia and had to device a plan, they started hating the Christians, including Armenians who wanted reform from Ottoman high ranks.

I can almost say that the Ottoman empire was already gone in the 1800’s and the rebelions within it started in the 1700’s.

And the same way as the violances which predated the genocide lead to it, the Armenian genocide lead to the jewish holocost and many others which took place in the last few decades.

Re: Stan, no offense indeed.

I read Vartan Motiossian’s study of the evolution of the word yeghern BEFORE 1915. He concludes study as follows: “Before 1915, then, yeghern was solidly established, both in dictionaries and in literary texts, with the meaning of “crime.” The genocide would bring the use of the word to a higher level.” and that being that the word Yeghern meant the Armenian Genocide. I do not think that there can be any dispute to my assertion.

It is my gut feelings that I voice for I do not have the resources nor do I have the academic preparation in matters relating to Armenian language. I doubt very much that even before 1915 the word Yeghern was synonymous with the commonly used Armenian word for crime, vojer – ոճիր. In fact I have no recollection of ever having come across the word yeghern to describe a crime, in the sense we ordinarily understand crime. Vartan may shed light on the use of these two Armenian words Yeghern and Vojer for crime.

One of the most fascinating books I have read is Antranig Dsarougian’s “Sere Yegherni Mech”, which literary means “Love During the Yeghern”. I hope that one day someone translates the book in English. I believe it will make one fascinating and informative reading. Out of curiosity, I wonder how would the readers translate the title of the book? I doubt it could possibly be “Love During the Armenian Genocide” for a novel.

We have a unique Armenian word for the Armenian Genocide, Yeghern. The Jews have their unique word as well, as I understand it to be the Hebrew word Shoah. The word in holocaust in English language has now to mean the extermination of the Jews even if not capitalized. We do not have such a word in English. I have opted for the word THE CALAMITY. Most will differ and would prefer to use Armenian Genocide instead. That is perfectly fine and understood. However, the word Yeghern will continue to reverberate in me deep-seated feelings that the word tseghabanoutium will never do.

From: Genocide and Gross Human Rights Violations in Comparative Perspective

By Kurt Jonassohn, Karin Solveig Björnson

“Scholars of comparative genocide studies soon applied this new term [genocide] to genocides that had occurred since antiquity. This practice was objected to by some less than inspired critics on the grounds that a phenomenon could not exist before it had a name. That a phenomenon has to have a name in order to exist is too ridiculous a proposition to require further rebuttal.”

Since at least the 1880’s yeghern and vojir have been synonymous. They meant crime. There is no point in making such a big mystery out of yeghern, although the emotions attaching to it that Vahe Apelian reports are very moving to hear about and that feeling is widespread. When used in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, yeghern meant the “crime of crimes”, genocide–yes, genocide–even before Raphael Lemkin coined the word! That is the point. See the quotation above from the Jonassohn/Björnson book. You don’t need to have or use the word genocide to recognize and name the genocide you have just survived! That is my point in presenting the quotation from the book.

Armenians knew that they had just suffered a genocide and did not just wring their hands and remain content to refer to it as a calamity, although they gave it that name too. But as to the main name they gave it: It was a name that was designed to stick and be a lasting indictment of the criminals who planned their extermination. That was the point. But in the last few years, because of the orchestrated campaign of Turkish denialists to sow confusion and cover the CUP’s fingerprints all over the Armenian Genocide and falsify the meaning of the word, yeghern has been redefined as “calamity”. This linguistic tsunami has swept even many Armenian academics, intellectuals, commentators off their feet to the point that they have helplessly volunteered to propagate the same harmful nonsense.

No, it is not “meaningless chatter” to defend the true meaning of Medz Yeghern. If that is “meaningless chatter” then we can kiss our language and our history goodbye. . . .

for what it’s worth:

The word holocaust was used to describe Armenian atrocities in the September 10, 1895 New York Times headline.

The word holocaust signaled that something extraordinary was happening to the Armenian people.

Nobody owns the word.

Over twenty countries have accepted Lemkin’s definition of what was done to the Armenians and call it the Armenian Genocide. The International Association of Genocide Scholars calls it the Armenian Genocide. The Turks reading this page are hoping that we will call it something else – anything else – just free them from the word genocide. Not a chance.

This is an interesting article. However, the author Mr. Matiossian may have also wanted to reference Ajarian’s masterpiece the Dictionary of Armenian Root Words which he penned in the 1920s. There (volume 2, page 17 in the 1979 reprint) Ajarian states that the word means “crime” (vochir, ոճիր) in modern Armenian literature, and meant “misfortune (portsank, փորձանք), evil (charik, չարիք” in the classical Armenian sense.

Indeed, the conclusion of the author Mr. Mattiosian is correct and is in tune with Hrachia Ajarian’s explanation of this word. See this link: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=7&query=եղեռն

Let me add one more important element to this article. It turns out that there is indeed an Armenian word (a single word) մեծեղեռն which is an adjective meaning “heinous”. I first came across this word in Father Haroutioun Avkerian’s 1821 English-Armenian dictionary, under the headword “heinous”. Here (on page 421) we read the following definition: Heinous ածական. Անագորոյն, ապիրատ, մեծեղեռն, անգութ, տմարդի, սաստիկ, անհնարին, դժնեայ, ահագին, սոսկալի։

Mind you. This dictionary is printed in 1821, about 100 years before 1915. And what does “heinous” refer to? Indeed, to a crime. Therefore, even in the 1820s մեծեղեռն as an adjective referred to the quality of a crime: its being heinous.

Doing some further cross-checking, it turns out մեծեղեռն has an entry in the Նոր Հայկազեան Բառարան (NHB 1836-1837) and in Jakhjakhian’s Armenian-Italian Dictionary (Բառգիրք ի բարբառ հայ եւ իտալական, JB 1837) we have: Մեծեղեռն ա. Scelleratissimo.

Scelleratissimo in Italian translates as “most wicked,” according to Google Translate, and as “Very wicked” according to Wiktionary. All of this corroborates the author’s point that Մեծ Եղեռն refers to a Great Crime. But this goes even deeper — մեծեղեռն itself is a word from Classical Armenian, and it refers to adjective describing “the Most Wicked” of Crimes!

For NHB 1836-1837 see: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=26&query=մեծեղեռն

For JB 1837 see: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=54&query=մեծեղեռն

It is also noteworthy that Simon Kapamajian in his Նոր բառագիրք հայերէն լեզուի (1910, Constantinople) has an entry as well: Մեծեղեռն ածական. չարագործ։ Չարագործ meaning “evil-doing” in Armenian.

Malkhasiants, too, has an entry for մեծեղեռն and notes it as an old or archaic term: շատ եղեռնական, շատ եղեռնագործ։ The last dictionary to have the word seems to be Jizmejian’s 1954 work.

For Kapamajian see: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=14&query=մեծեղեռն

For Makhasiants see: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=6&query=մեծեղեռն

Finally, and importantly, Father Bedrossian’s seminal 1875 New Dictionary Armenian-English (Venice) has an entry:

Մեծեղեռն a. execrable, abominable; very wicked, heinous;

մեծեղեռն ամբարշտութիւն, horrible crime;

մեծեղեռն յանցանք, crime.

Clearly, Մեծեղեռն is an adjective used to describe a “very wicked” or “heinous” crime.

For Bedrossian 1875 see: http://www.nayiri.com/imagedDictionaryBrowser.jsp?dictionaryId=16&query=մեծեղեռն