I remember the first time I entered the Armenian All Saints Apostolic Church in Chicago. My parents, brother, and I had recently immigrated to the United States of America. As DPs (Displaced Persons) from Europe, we came on a battle ship used for transporting immigrants. Church members introduced us to the community and other DPs. I was a kindergartener and, therefore, “old enough to sit through church service,” my parents had smilingly said to me before we entered the church. I sat between my mother, who was cradling my brother in her arms, and my father. There were rows and rows of pews, and so many people sitting in them—ladies, with scarves on their heads, some with hats, dressed in their Sunday best, men in suites, and children all dressed up. Some ladies, like my mother, were also cradling babies in their arms. I gazed with wonder at the large, stained glass windows that were on the right and left sides of the church. With the sun shimmering through them at different times, the windows were magical to me. I stared at the flickering candles slowly melting in the sand-candle-stands. I looked intently at the (Raphael) painting of the Madonna and Child above the altar. It was large and hauntingly beautiful. I glanced at the paintings hanging on the walls just past the side altars, and asked my father who the men depicted in them were. He pointed to the painting on the left wall and whispered, “He is Saint Sahag Bartev.” Pointing then to the one on the right wall, he whispered, “And he is Saint Mesrop Mashdots.” Although the priest spoke in Armenian, I didn’t always understand what he was saying, what the other men at the altar assisting him were chanting, or what the choir was singing. I only knew that I liked the sights and sounds and scent inside this lovely place that made me feel so good. Although we lived far from the church, I liked coming whenever my parents were able to attend. Sometimes we walked, which took such a long time that I would get tired, so my father would carry me the rest of the way. Other times, particularly in inclement weather, we took the bus, and then it was just a short walk to the church.

Eventually, when I was old enough and could walk or take the bus to church on my own, I would attend service by myself. Then one day, I joined the choir. I marveled at the sequined cape and slippers, the lace veil, and the robe the first time I put them on. With hymnbook in hand, I was now a member of the choir, and remained so for a few years. Over the years, our church and community experienced a number of changes, such as the church’s move from Chicago to Glenview, Ill., new clergymen, and more use of English to accommodate parishioners who did not speak Armenian. Women were no longer required to cover their heads in church, except when they took communion. There were the periodic arrivals of new immigrants and newcomers to the city, and some who left. However, there were things that remained the same, such as the church rituals and hymns, the paintings of the Madonna and Child and the two saints, the sand-candle-stands and stained glass windows. Until I was older, and had a family of my own, I did not give much thought to the importance of the clergyman’s role in the community other than performing church service and other church-related duties. Occasionally, though, it did cross my mind, especially as I became acquainted with a number of different clergymen, that some were more outgoing than others; that some seemed to exude more religiousness than others; and that some had a greater impact on the youth, and the congregation in general, than others did. At times, I wondered what it was that prompted these men to become clerics, because I had come to see that the path they chose was not an easy one, whether serving in a city, a town, or a village. When I asked a few of them how it was that they chose to become clerics, one said that he felt the calling to serve God when he was an altar boy; another said it came to him in a recurrent dream he had had when he was little; and another, who was of a higher ranking, pensively explained that it came about because of the poverty into which he was born. A celibate priest who had been working under extremely difficult and harsh conditions in a remote and primitive Armenian village had explained to me in his home there, a dank, dim, spartan hut: “My brother, whom I loved deeply, became gravely ill one day. We were children at the time, and he was my best friend and playmate. As I fearfully watched my brother growing weaker and weaker by the hour, despite the efforts of the doctor, and as I watched my grief-stricken parents and the whole family wailing and moaning at his bedside day and night, I became terribly frightened. Wanting to do something, but not knowing what, I began praying. I prayed with all my heart to God, beseeching Him to restore my beloved brother to health. After many, many days of praying, God at last heard my prayers. And so, in profound thankfulness, I offered my life to serving Him.” The priest had smiled as he joyfully uttered the last sentence.

During my early, formative years, and even in subsequent years, some of the clergymen who served our church, and some who served the other Armenian churches in the Chicagoland area, left deep and indelible impressions on me. As a result, they led me to understand better the importance of the Armenian clergyman’s role in a community, not only as a spiritual leader and teacher, but also as a guardian of our heritage. In our church, one such priest was the late Der Hayr (Reverend Father) Sahag Vertanessian, who had a reflective and congenial manner, and always made time to talk to people. He gave meditative sermons, and often provided inspirational reading material to those interested in such subjects. Another priest was the late Der Hayr Smpad Der Mekhsian, who possessed a welcoming and sunny disposition, gave exceptionally moving sermons, and had a smile and warm handshake for everyone. His home-blessing visits were always beautiful and extra-special occasions for our family.

At the Chicagoland’s Armenian Evangelical Church, the retired Reverend Barkev Darakjian was inspirational with his gracious and amiable manner towards both his parishioners and non-parishioners alike, and his promotion of Armenian cultural and educational events.

At the Saint James Armenian Church in Evanston, the late Hayr Soorp (Very Reverend Father/celibate priest) Varoujan Kabarajian left a deep impression on me with his kind and encouraging manner, particularly toward the youth—even those who were not members of his congregation. I was a high school student at the time when I had mentioned to the Hayr Soorp one day during a casual conversation at a community affair that, although I knew how to read and write in Armenian, I wanted to improve my skills. He nodded and then said with a smile, “You are welcome to attend my Armenian language class.” He was a fine teacher, and I learned much in his class. One day, years later, I bumped into the Hayr Soorp in one of the area supermarkets. He was carrying a grocery bag in each arm. After we greeted each other, he asked about my husband and family and announced in his usual jovial manner, “Well, I’m finished with my Easter shopping, so now it’s off to church to prepare Zadig (Easter) treats for the children…!” Learning what the Hayr Soorp was so happily and enthusiastically planning to do for the children at his church reminded me of the late Mkhitarist Fathers Luke (Arakelian), George, and Gregory. How happily and enthusiastically they too performed their duties at the delightful summer camp for boys and girls they ran years ago in Falmouth, Mass. One other person was the Armenian Catholic priest Hayr(Father) Yeghia, who worked devotedly and tirelessly, along with the Armenian Catholic nuns (the Armenian Sisters of the Immaculate Conception Order) in the villages in Javakhk, Georgia. These humble and dedicated clerics, and nuns, all had two qualities in common—Inspiration and Guidance.

The reflective and poignant homilies that were given in the Chicagoland Armenian community over the years by the Prelacy’s Archbishop Karekin Sarkissian, later His Holiness Karekin II, Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia, then His Holiness Karekin I (of blessed memory) Catholicos of All Armenians; His Holiness Aram I, Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia; the Diocese’s Archbishop Khajag Barsamian; and the late Reverend Movses Janbazian, director of the Armenian Missionary Association of America (AMAA) filled me with an even greater reverence for my Armenian heritage. All of these spiritual leaders spoke and interacted with the people in a humble, warm, and attentive manner. And, though they were from different orders and ranks, their sacred work was the same—the Fostering of the Armenian People and Nation.

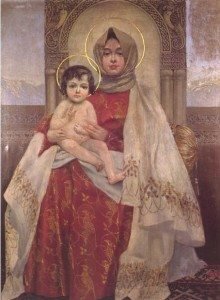

Years have come and gone, and with them many changes, but always one thing has remained constant—the unassuming splendor of the Armenian Church. As I entered our church in Glenview one Sunday, I took a seat behind a young immigrant family. The father was motioning to his little boy and girl to sit quietly, while the mother was cradling their infant in her arms—what a familiar, heartwarming scene it was! As the choir sang “Khorhoort khorin, anhas anusgispan… (O profound mystery, incomprehensible and without beginning…), I began reflecting upon the meaning of the ancient hymn—The Hymn of Vesting. Suddenly, I was distracted by a dull thump that came from the direction of the stained glass windows so iridescent and luminous in the light of the morning sun. No doubt, a bird had struck one of the windows. I hoped it was not injured, and then I gazed for a moment at the flickering candles—prayer offerings to God—in the nearby sand-candle-stand. As prayers and incense, chants and hymns, filled the church, I recalled my first visit to Armenia. It was during the days when God was banned from that part of the world. One of my relatives there had cautiously explained to me, after my visit to Holy Etchmiadzin, that despite the dire consequences for non-compliance, there were those devout souls who, in the refuge of their minds, still prayed and sang the sharagans (hymns). One of those devout souls, who had expressed his religious feelings through some of his art, had been Vazgen Surenyantz. Several of his works, among them his 1896 painting of the Madonna and Child, had been rescued from the hands of the Soviets by the clergy in Etchmiadzin.

My thoughts now turned to the elderly woman who was sitting in the pew a couple of rows in front of me. After painstakingly adjusting her headscarf, she struggled to her feet and laboriously walked down the aisle to receive communion. She reminded me of one of the genocide survivors I had interviewed years earlier. Then, as the choir sang the “Aghotk Deroonagan” (Lord’s Prayer), I wondered, as I looked about me at the congregation, many of whom were descendents of genocide survivors, how such a downtrodden, Christian people, who had suffered great tragedies through the centuries—invasion, domination, persecution, slavery, mass murder, and destruction—continued, and continues still, to maintain not only their identity, but their religion as well. What is it that gave them, and still gives them, the fortitude to uphold the heritage of their forefathers?

As the days and weeks passed, I continued to consider the question I had that day in church. Then one evening, while sitting at my desk and looking through a collection of books, booklets, pamphlets, and articles, I realized that the answer lay in our historical figures and their contributions, which through the ages have, knowingly and unknowingly, impacted us as a people and nation. Krikor Bartev Bahlavuni, known as Saint Gregory the Illuminator (circa 239-326), was instrumental in converting pagan Armenia to Christianity and was the first Catholicos of the Armenian Apostolic Church; Saint Sahag Bartev (348-439) was Catholicos during Armenia’s Golden Age of Literature (5th century) and encouraged the creation of the Armenian alphabet by Mesrop Mashdots; Saint Mesrop Mashdots (361-440) was the inventor of the Armenian alphabet in A.D. 404 and opened the first Armenian school; Ghevont Yerets (5th century) was the valiant priest who not only preached the Gospel and translated holy writings, but fought and was martyred in the Battle of Avarair—a struggle for religious freedom; Yeghisheh (5th century) was a historian and celibate priest who authored the History of Vartanank, a book on the Battle of Avarair; Movses Khorenatsi was a bishop and historian, author of The Genealogical Account of Great Armenia, also known as The History of Armenia; Ananiah Shirakatsi (7th century), referred to as Vartabet (celibate clergyman) by Archbishop M. Ormanian, was an astronomer, mathematician, scientific researcher, and author (among his works are the Book on Arithmetic and Astronomy and Calendar); Saint Grigor Naregatsi (950-1010) was a clergyman and author, and among his greatest of works is The Book of Lamintations, also known as The Book of Prayers or Narek; Saint Nerses Glayetsi, known as Nerses Shnorhali (1100-1173), was a clergyman, composer, and author of “sharagans (hymns), canticles, and lyrics,” whose prayer, “Havadov Khosdovanim” (I Confess with Faith) has been translated into 36 languages; Mekhitar Kosh (1130-1213) was a celibate priest and “compiler of the first Armenian Corpus Juris or the Code of Civil and Canon Laws”; Mugrditch Khrimian, (1820-1907), Catholicos, known endearingly as Khrimian Hayrig (Father), was a revered religious leader of the Armenian Revolutionary Movement, teacher, publisher, and author; Karekin Servantzdiantz (1840-1892), a student of Khrimian Hayrig, became a bishop, and was a writer, preacher, patriot, and collector and compiler of Armenian allegories, anecdotes, fables, and folk-tales, thus rescuing them from oblivion; Maghakia Ormanian (1841-1918) was a clergyman, Patriarch of Constantinople, scholar, teacher, writer, lecturer; Komitas Vartabed (1869-1935) was a renowned clergyman, teacher, vocalist, musician, composer, and musicologist.

Then, opening one of my folders to look through some notes I had taken on the topic of the Armenian Church, I came across a fragile, yellowed copy of an article I had saved titled “Women in the Armenian Church” by Yedvard Gulbekian, and published in the Armenian paper Hye Sharzhoom in April, 1982. The article began:

“The attempted genocide of the Armenians during the first world war resulted in much more than the loss of a large proportion of the Armenian nation, its material culture, and the Armenian plateau, for the chaos caused by murder, hunger, exposure, disease and invasion, severely disrupted the continuity of customs and traditions, and stunted the proper developments of Armenian institutions during this century.

“Fortunately, much of the musical heritage of Armenia had been saved thanks to the selfless efforts of Komitas Vardapet, and one significant folk epic, Sasountsi Davit, had been committed to writing by Bishop Garegin Srvandztyantz in the 19th century, but much else was irretrievably lost. In particular, the church of Armenia suffered losses that undermined its structure and theology in such a subtle manner as to consign the pre-1915 situation to oblivion.

“One of these victims, now submerged in the national consciousness, was the ministry of women in the church… Its existence was brought to light in 1974 during a historical exhibition in Tehran. This carefully prepared display of Armenian costumes through the ages…included the vestment of a 19th-century Armenian deaconess from Constantinople… That deaconesses were not in minor orders, as some have claimed, but members of the clergy as indicated by the circumstances that they were ordained by bishops… The church of Armenia, which had women ministers until their demise as a consequence of the action of the Ittihad party during the first world war, has forgotten that they ever existed… The late Nicolas Zernov, a prolific writer on church affairs, wrote in 1939 how impressed he had been when personally present at the Eucharist in the Armenian church of St. Stephen in Tiflis ‘where a woman deacon fully vested brought forward the chalice for the communion of the people.’”

Wanting to know more about this intriguing topic, I contacted St. Nersess Armenian Seminary in New Rochelle, N.Y. Father Stepanos Doudoukjian (now at St. Peter Armenian Church in Watervliet, N.Y.), answered my questions and provided me with a copy of Fr. Abel Oghlukian’s book titled The Deaconess In The Armenian Church–A Brief Survey. Seminary faculty member Prof. Roberta R. Ervine sent me a copy of her article published in the St. Nersess Theological Review titled “The Armenian Church’s Women Deacons.”

In his book, Father Oghlukian writes: “The development of the office of deaconess in the Armenian Church can be divided into four historical periods: 1) Greater Armenia in the fourth to eighth centuries. There are uncertain references in the canons to women who have a claim to be present at baptisms. 2) Eastern and Cilician Armenia in the 9th to 11th centuries. There the term deaconess is employed in ritual texts (mastoc) of ordination. 3) From the 12th century there are literary references and rites for the ordination of deaconesses in liturgical texts, first in Cilicia and then in Eastern Armenia. 4) The renewal of the female diaconate in the 17th century.”

The book states that the deaconesses’ vestments, as illustrated in records from the 12th century, “bore a small metal cross suspended from their brow and a stole from their shoulder… In more recent times, photographs of the 19th and 20th centuries illustrate them dressed in a robe during the liturgy and vested in a white veil almost from head to foot.” Contained in the book are the names of female scribes, some of whom were “Goharine who copied Grigor Narekaci’s Prayerbook, the hermit Susan who copied Khorenaci and Eghishe, etc. … the scribe of Matenadaran Ms. No. 39…included her name in the title in an acrostic which reads ‘Ustiane sarkavag’ (deacon).”

In her article, Ervine includes the names of 23 deaconesses of the Armenian Apostolic Church and details the religious communities and various locations the deaconesses have served the Armenian Church from the 17th century, and, in some places, where they continue to serve the church in the 21st century. The names of the religious communities or localities are: St. Catherine’s Nunnery, New Julfa, Iran (founded 1623 and closed in 1954); St. Stephen/Saint Stepanos of the Holy Virgins Church, Tiflis, Georgia; the Kalfayan Sisterhood, Istanbul, Turkey, founded in 1866 (“the ‘last’ currently in service, Sister Hripsime Sasunian, was ordained by Patriarch Snorhk Galustean in 1982”); Byblos, Lebanon; the Cathedral of Holy Theotokos, Astrakhan, Russia; the village of Seoleoz, Diocese of Bursa, Turkey; the Armenian community in Jazlowiec, Poland/Ukraine; the Armenian community in Argentina.

“For some of the women deacons,” Ervine writes, “we have descriptions of the activities in which they were engaged; for some, there are data concerning their ordination; for others, the fact of their presence in a given moment or situation is merely mentioned as something taken for granted and requiring no elaboration… Armenian women in the deaconate have offered centuries of service both illustrious and humble—and certainly various.”

Interestingly, just as the Kalfyan Sisterhood of Istanbul (which included nuns, deaconesses, and arch deaconesses) and the other religious or monastic communities listed above, the Armenian Sisters of the Immaculate Conception, a religious order of Armenian Catholic nuns, established in 1847 in Constantinople, dedicated themselves not only to God and church, but to the Armenian Nation as well. Both the Armenian Deaconesses and the Armenian Catholic Sisters promoted education, ran schools and orphanages, and tended to the needs of the poor, the downtrodden, and the bereaved. The Armenian Sisters of the Immaculate Conception continue to serve the Armenian People.

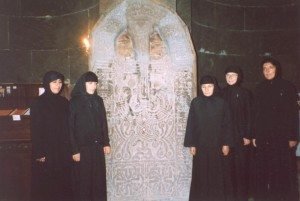

Currently, there are a small number of Armenian nuns serving the Armenian Apostolic Church in Armenia. Established in the early part of the 21st century, their order is known as the Sourp Hripsimyants Order. Dressed in long black habits and head coverings, their duties involve praying, serving the monastery’s abbot, visiting neighborhood families, cleaning the church and its property, and preparing meals. They reside in the vanadoon (monastery) at the Sourp Hripsime Church in Etchmiadzin. The church is considered one of the “oldest historical monuments of Armenian architecture and the second church built by St. Gregory the Illuminator during the first quarter of the 4th century…and rebuilt in 618.”

Included in Father Oghlukian’s book, as well as in Ervine’s article, are a number of fascinating photos, including one of “Protodeaconess Sister Hripsime Aghek-Tahireanc in her liturgical vestments, Jerusalem, 19th century (from H.F. B. Lynch’s book titled Armenia: Travels and Studies, Vol. 1),” and a photo of “the doors of the main entrance to the Cathedral of Holy Etchmiadzin, donated by Sister Hripsime Aghek Tahirieanc. The inscription reads: ‘In memory of protodeanconess Hripsime Aghek Tahireanc, 1889.’ On the bottom: ‘Ingenieur Nicolas Grigorian.’”

As I put away the books and material I had been reading and looking through, I began thinking about the words Bishop Karekin Servantzdiantz had written: “Patriotism is a measureless and sublime virtue, and the real root of genuine goodness… It is a kind of virtue that prepares a man to become the most eager defender of the land, water, and traditions of his fatherland.”

References

The Pillars of the Armenian Church, compiled and edited by Dikran H. Boyajian, 1962, Baikar Press, Watertown, Mass.

The Deaconess in the Armenian Church, A Brief Survey, by Father Abel Oghlukian, 1994, St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, New Rochelle, N.Y.

“The Armenian Church’s Women Deacons,” by Roberta R. Ervine, St. Nersess Theological Review 12 (2007).

Armashi Dbrehvankuh, by Parouyr Mouradyan and Astgheek Mousheghyan, 1998, Yerevan, Armenia.

A Brief Introduction to Armenian Christian Literature, by Archbishop Karekin Sarkissian, 1960, Faith Press, London; 1974, A Michael Barour Publishing, USA.

An Interpretation of the Holy Liturgy or Soorp Badarak of the Armenian Apostolic Church, by Reverend Gorun Shrikian, the Armenian Apostolic Church of America, New York, N.Y.

A Walk Through the Divine Liturgy of the Armenian Church: A Guide to the Badarak,

by Very Reverend Father Daniel Findikyan, 2001, Diocese of the Armenian Church of America, New York, N.Y.

St. Grigor Narekatsi–Speaking with God from the Depths of the Heart, translated by Thomas J. Samuelian, poetic editing by Diana Der Hovanessian, 2002, printed in Armenia.

The Book of Lamentations by Grigor Narekatsi (in Armenian), 1979, Yerevan, Armenia.

Soorp Etchmiadzine, edited by Grigor Khandjian, 1981, Etchmiadzin, Armenia.

“Year of the Armenian Woman 2010,” Pontifical Message of His Holiness Aram I, Catholicos of the Great House of Cilicia, Dec. 31, 2009, Antelias, Lebanon.

Hye Sharzhoom Armenian Newspaper, April, 1982 issue, Fresno, Calif.

The author would like to express her appreciation to the following for kindly responding to her inquiries regarding the Armenian Church and for graciously providing literature on the subject:

St. Nersess Armenian Seminary, New Rochelle, N.Y.

Deacon Levon Altiparmakian, director of St. Nersess Armenian Seminary.

Father Stepanos Doudoukjian

Professor Roberta R. Ervine

Very Reverend Father Nerses Khalatyan, Etchmiadzin, Armenia, for the book Armashi Dbrehvankuh (The Armash Seminary), and literature on the Armenian Deaconesses.

Dr. Garen Koloyan, Yerevan, Armenia, for delivery of the literature provided by Father Khalatyan.

The author would also like to express her appreciation to the following clergyman for kindly responding to her inquiries on the Armenian Church:

Reverend Father Tavit Boyajian, Sts. Joachim and Anne Armenian Apostolic Church, Palos Heights, Ill.

Very Reverend Father Aren Jebejian, St. Gregory the Illuminator Armenian Apostolic Church, Chicago, Ill.

Reverend Father Hovhan Khoja-Eynatyan, St. James Armenian Church, Evanston, Ill.

Reverend Father Zareh Sahagian, Armenian All Saints Apostolic Church, Glenview, Ill.

D. KNAR & FRIENDS

This is wonderful.

Deep & true like all your work.

THANKS especially for remembering FATHER VAROUJAN.

FATHER VAROUJAN, May We All Meet Again !

MIKE ADAJIAN

Saint James Church, Evanston, USA

Knarig, thank you for a wonderfully written and researched article. Having also attended All Saints Apostolic Church when it was in Chicago, you brought back a flood of memories. Our beautiful old church, magnificent and majestic, filled with incense, ancient chants and hymns, and illuminated in a rainbow of colors streaming from the huge jeweled windows. I, always wearing a dress, a hat, and of course gloves, sat next to my grandfather in the first pew on the left side….”Hayrig” Markar’s pew. You continued my journey down memory lane naming the various religious leaders who, as you stated, affected us in many ways. Although all left an indelible mark, it was Hayr Sourp Varoujan from St James who probably molded my life the most. I too, was a recipient of Hayr Sourp’s Armenian lessons, which also included being mentored by him–until another institution of higher learinng took his place i.e. college. Aside from the memories, you educated me with so much history and previously unknown information. Thank you for continuing to write such quality articles…as always, I look forward to seeing what will be your next topic or literary piece, be it educational, fictional or poetic.

Dear Knarik,

I want to congratulate you on writing such an informative and educational article. I can not believe the wealth of this information. It is a must save paper for me for future refrence.

This is a great history lesson for many people and I hope some young people will read this and learn from it. I met you a few years ago in Providence when you and your husband attended our Govdoonzi Christmas party which continue to do each year. I also follow your many stories about your visits to Armenia and telling us how life really is there. You have a great heart and it shows through your writings. May you enjoy God’s graces and continue with your fine work.

Sincerely,

Joyce Yeremian

Thank you and God bless you for writing this VERY informative article.Knarik you’ve done a great service to our nation,thank you again!!!

Knarig,

I just finished your wonderful article called “Shephards of the Nation”. It was a beautifully written, scholarly piece and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. The topic is also very timely with all the debate going on in the Catholic Church about ordaining female clergy. It was surprising to me to know that had already occurred in the Armenian Church.

Brava! I’ve learned two things today. One, part of my religious history and two, to keep my eyes open so that I don’t miss your next article.

Dear Knarig, I am so proud to now you, You are my brave sister, God bless you for good work you do for Armenia and Armenian puples in the world. Keep up the good work, God save you for Armenian pupels. I wish you health and happiness.

Brotherly Love.

Kevork Gulluian

P.S. sorry for my English and miss speling

Dear Ms. Meneshian,

Thank You for a wonderful article. It is so historical and educational. I was very pleased to learn (for the first time) that our historical church had deaconesses that help the church and the Armenian community, and some still educate our children all over the world and carry very important role. I was never satisfied with the role of women in our present churches in United States as Ladies Auxiliary, who just prepare food for the occasions at the church, since I know there is more then that they could offer. I hope your article and the knowledge of the Armenian deaconesses will strike a cord with the church administrations throughout and more women will be included in church functions and decision making roles. I believe that their contribution specially to the Armenian communities will be priceless.

I look forward to more inspirational articles from you.

Dear Mrs. Meneshian,

Beautiful article ,I emailed it to my loved ones .

Thanks again and God bless.

Krikor.

Dear Ms. Meneshian, Your article has moved me deeply. Thank you for sharing this wonderful journey. Աստուած պահէ մեր Հայաստանեայց Եկեղեցւոյ եւ մեր պապենական ազգին ~

YOUR ARTICLE WAS MOST INFORMATIVE. MORE RELEVANT WAS YOUR REACHING OUT TO ALL ASPECTS OF OUR COMMUNITY IN THAT YOU MENTIONED WITH REVERENCE BOTH ASPECTS AND INDIVIDUALS RELATED TO PRELACY AND DIOCESE. YOU HAVE BROKEN THE STIGMA OF A DIVIDED ARMENIAN CHURCH IN AMERICA. WE NEED MORE INDIVIDUALS LIKE YOU DECLARING THAT THERE IS ONLY ONE ARMENIAN CHURCH IN AMERICA WITH DUE RESPECT FOR ALL ARMENIAN CLERGY STARTING WITH THE 2 CATHOLICAI STARTING WITH HOLY ETCHMIADZIN AND THE HOUSE OF CILICIA. BRAVO FOR AN OUTSTANDING SERVICE.–JOHN MANUELIAN,WINCHESTER,MA.

Dear Readers,

Thank you so very much for your comments about “Shepherds of The Nation.” I am deeply touched by your kind and encouraging words.

Again, Thank You!

Knarik O. Meneshian

I had heard of women serving the altar during WWII because most of the men were at war, but I never realized how extensive their involvement was historically. Given this history can anyone please explain to me why we are not training young girls to be deaconesses now? Seems like a waste of talent.

I patiently read all of the article unaware of most of the facts presented there-in!

It was thought provoking, at a minimum. Having said that and with that article,

your work is commensurate to Murad’s “Raffi”!

The The comments made by the readers expressed my views well. Thx, Knar. I too have received from your work. Hike

Dear Knarik , I* was so happy to read and see your picture in the internet. Your lecture was very interesting and informative. Now I live in Yerevan and hope to see you someday soon. With blessings to you and your family.